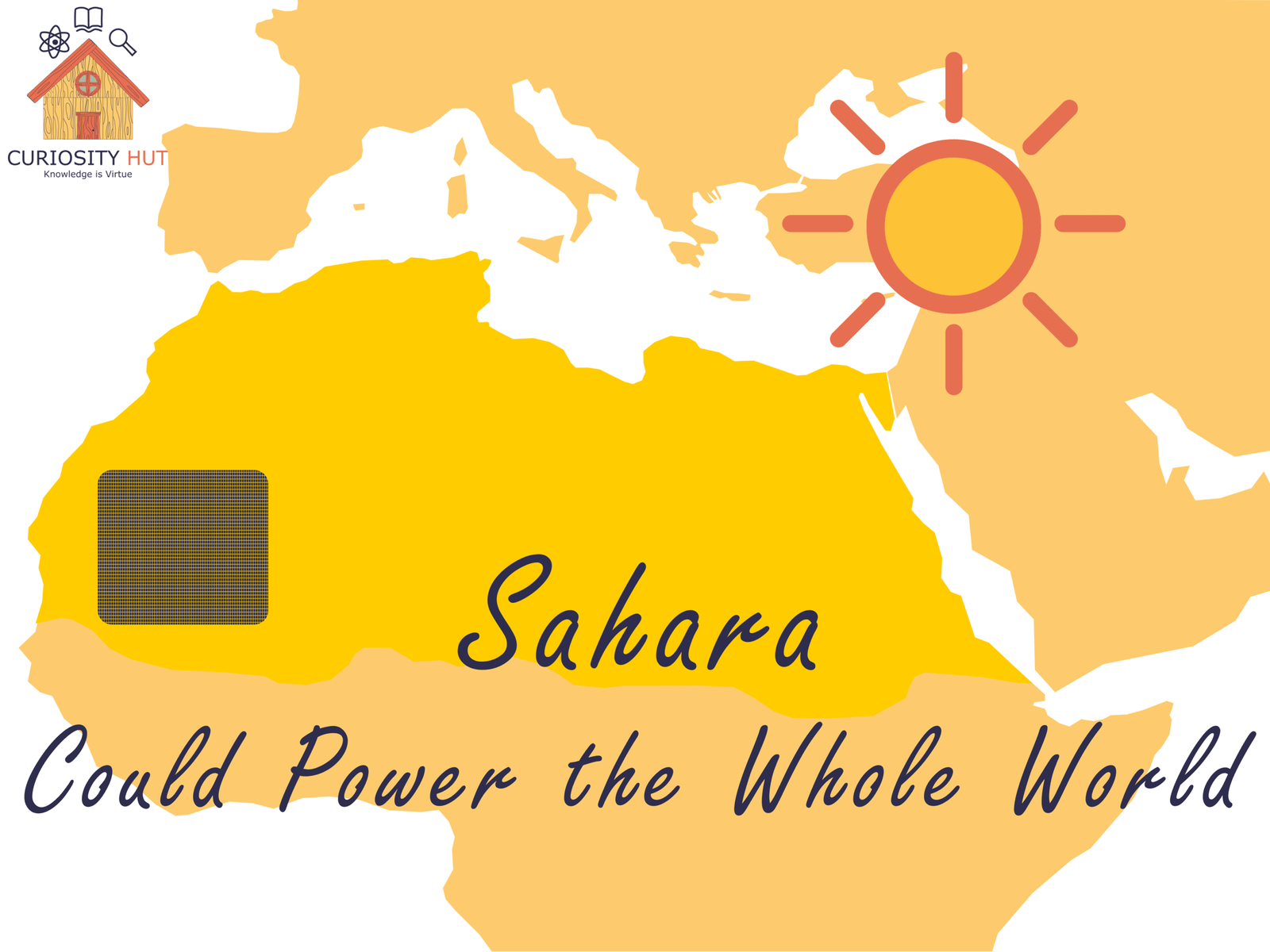

In the heart of North Africa lies the world’s sunniest wasteland: the Sahara Desert. Every square meter receives about 2,000 kilowatt-hours of sunlight each year—roughly what a household fridge uses in that time. Cover just one-tenth of this vast expanse with solar panels, and in theory, you could power all of humanity. Yet the desert remains empty, its sunlight unharvested. Why hasn’t the world’s brightest idea taken root in the world’s hottest place?

How Solar Panels Work (in a Nutshell)

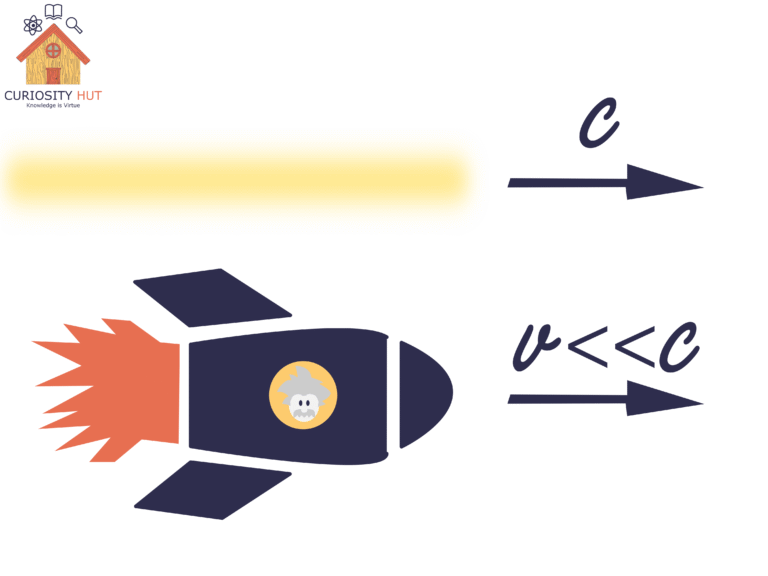

To understand the desert’s resistance, we need to know what solar panels actually do. Each panel is a thin sandwich of silicon, metal, and glass that turns sunlight into electricity. Inside the silicon, atoms hold electrons like seats in a theater. When sunlight hits, particles of light—photons—knock electrons loose. The freed electrons flow as an electric current, powering devices.

This is the photoelectric effect, the discovery that won Albert Einstein his Nobel Prize in 1921. It revealed that light is made of discrete packets of energy, not just waves—a principle that would eventually make solar power possible.

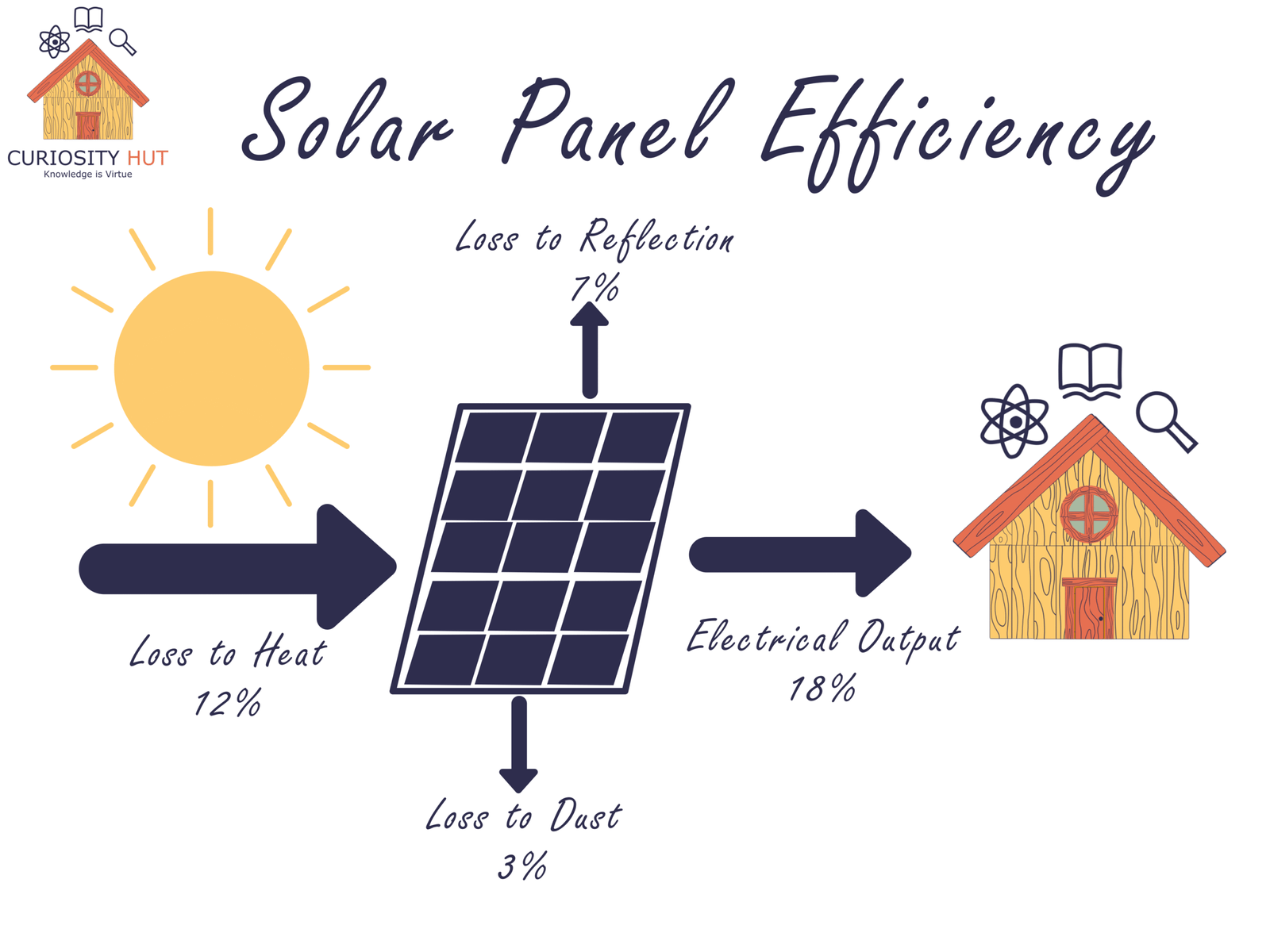

In practical terms, modern panels convert about 20% of sunlight into electricity. Each square meter under desert sun produces around 200 watts—enough for a laptop and a small fridge. Multiply that by the Sahara’s nine million square kilometers receiving over 4,000 hours of sun a year, and the potential energy is staggering.

So, the physics works. The sun delivers. Yet the desert fights back.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.

The Desert Fights Back: Practical Challenges

At first glance, the Sahara looks perfect: endless sunlight, open land, no neighbors. But nature has other ideas.

Heat: When sunshine becomes the enemy

Panels love sunlight but hate heat. Every degree above 25 °C cuts efficiency by 0.4%. Sahara panels can hit 70–80 °C, slashing output by a third and accelerating wear. Imagine leaving your laptop on a sunbaked dashboard—it works, but not for long. Cooling millions of panels across the desert would require nearly as much engineering as building them.

Dust: The slow, gritty sabotage

A thin layer of dust—just 1/20th of a millimeter—can block 40% of sunlight. Sandstorms scour panels like sandpaper. Cleaning requires millions of liters of water per multi-gigawatt site, roughly what a city of half a million drinks daily. Robots help, but they’re expensive, energy-hungry, and not immune to grit.

Water: Scarce, precious, inconvenient

PV panels need water mainly for cleaning. CSP plants, which use mirrors to boil water and spin turbines, require 800–1,000 liters per MWh—a luxury the Sahara can’t easily supply. It’s like trying to run a steam engine in a sandpit.

Transmission: Too far from the plug

Electricity weakens as it travels. Sending power from central Sahara to Europe (~3,000 km) loses roughly 10% in the lines and demands billions for infrastructure. Imagine trying to pipe soup across continents—by the time it arrives, some has cooled, and the piping wasn’t cheap.

Scale and logistics: The tyranny of size

Covering just 1% of the Sahara—an area the size of Portugal—would require 60 billion solar panels and cost tens of trillions of dollars. Add factories, roads, storage, and grid hubs, and the “simple” plan becomes a massive engineering puzzle.

When Clean Energy Isn’t Harmless: Environmental Costs

Even if engineers solve heat, dust, and water problems, the desert still has another set of hurdles: its fragile ecosystem and local climate.

Habitat loss: The desert is alive

Sand may look empty, but it hosts snakes, lizards, insects, and plants adapted to survive extreme heat and drought. A single utility-scale farm can sprawl 5–10 km², fencing off habitat and fragmenting migration routes. Bulldozing the desert may appear efficient, but it disrupts a finely balanced ecosystem.

Soil and albedo changes: Shading more than the ground

Panels are dark and absorb the sunlight that normally reflects off sand. Changing the surface’s albedo can raise local temperatures and shift winds. Models suggest covering 20% of the Sahara could increase air temperatures by 1–2 °C, subtly altering rainfall patterns. Even clean energy has ripple effects.

Manufacturing, cleaning, and constructing panels use water and chemicals. One panel consumes hundreds of liters in production and contains materials like cadmium or silicon tetrachloride, which must be handled carefully to avoid contaminating soil or groundwater.

Wildlife mortality: Unseen casualties

CSP plants’ solar towers focus sunlight to super-hot points. Birds flying through can literally get fried. At California’s Ivanpah plant, thousands were injured or killed by the beams, and insects get trapped too. Even minor changes can cascade through food chains.

Microclimate effects and indirect impacts

Large solar arrays alter convection, humidity, and surface winds. Roads, transmission lines, and maintenance stations invite human intrusion, invasive species, and further habitat fragmentation. The desert’s seeming emptiness hides a complex system; even small disturbances have outsized consequences.

Weighing the Trade-Offs: Why the Sahara Isn’t Our Giant Solar Farm

The Sahara tempts us with brilliance. Sunlight there is so intense that a square meter collects enough energy in a year to run a fridge non-stop, and just 10% of the desert could, in theory, power the entire world. The math is seductive, the imagery irresistible.

But the desert fights back. Heat saps efficiency, sand smothers panels, water is scarce, and sending electricity thousands of kilometers eats away at what we capture. And covering this fragile ecosystem threatens wildlife, alters soil and microclimate, and introduces hidden water and pollution costs.

The solution isn’t one colossal desert of panels, but many smaller, smarter interventions. Rooftops, parking lots, brownfields, and floating solar on reservoirs offer energy close to where people live. Advanced materials, dust-tolerant designs, and efficient storage amplify yield without bulldozing ecosystems.

The dream of the Sahara reminds us of both our ambition and our limits. It asks not just “can we capture all that energy?” but “should we?” And the answer lies in balance: ambitious yet careful, innovative yet humble, illuminating a path toward energy that truly respects the world it powers.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.