The secret math and physics hiding in your hand.

Take a look at the can on your desk, or the one rattling in your fridge right now. It feels so ordinary, you can’t notice it. A neat little cylinder, shiny, light, and unremarkable. But that humble can is a minor miracle of design.

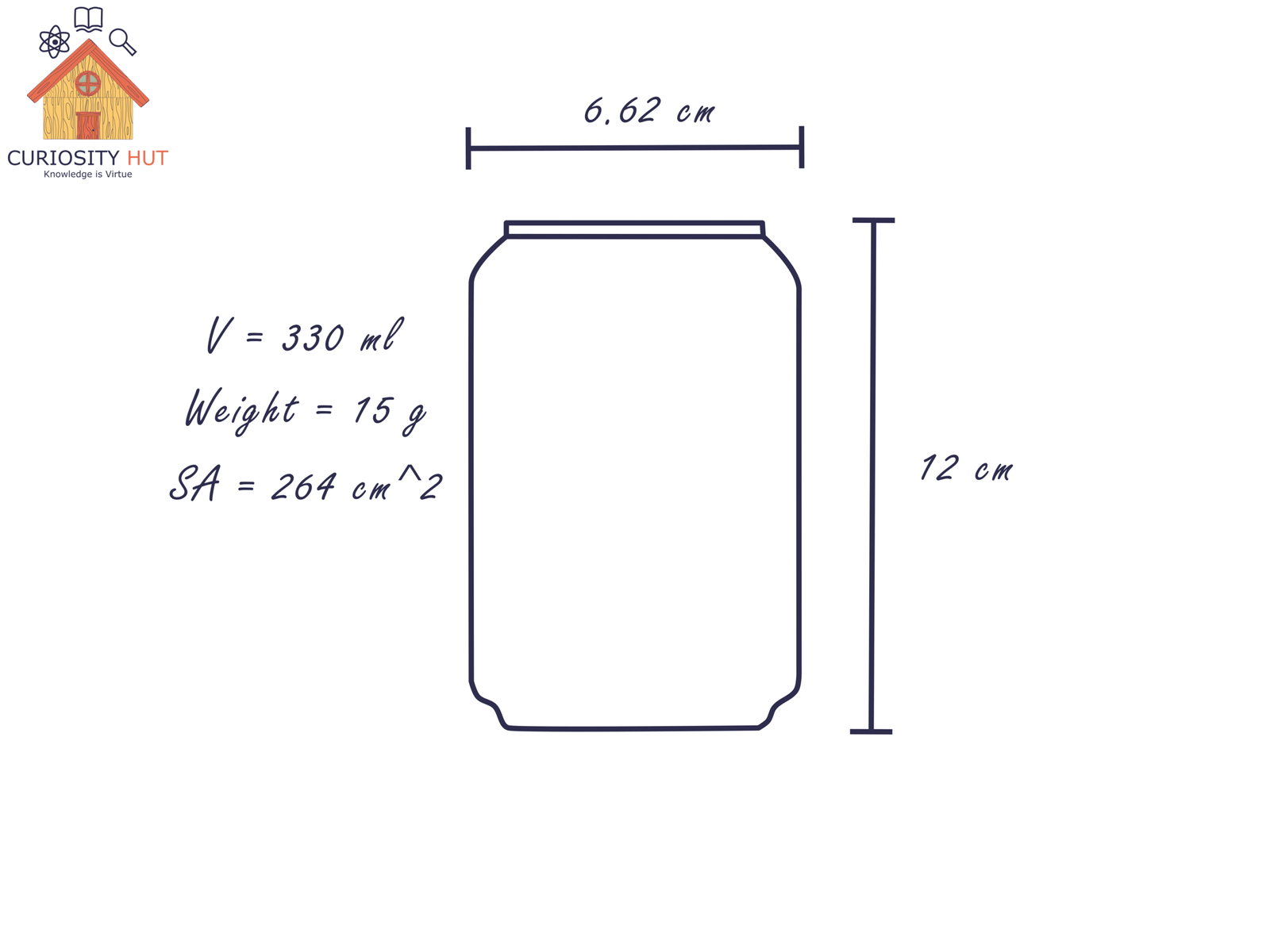

Every standard soda can holds 330 milliliters of liquid, stands about 12 centimeters tall, and weighs 15 grams of aluminum. Each year, the world churns out around 280 billion of them. That’s about 80 billion in the U.S. alone.

Add that up and you get 4.2 trillion grams of aluminum. If you melted all those cans into one giant block, you’d have enough metal to build more than 60,000 Boeing 747 jumbo jets. Not bad for something that usually ends up in the recycling bin.

And here’s the kicker: every single can is shaped the way it is for a reason. Engineers had options: sphere, cube, cylinder, tuna-can squat. But one shape survived the battle of physics, math, and practicality.

The Sphere Problem

At first glance, a sphere seems like the obvious winner. It’s nature’s most efficient container: for a given volume, it uses the least surface area. If soda cans were spheres, they’d need about 15% less aluminum than today’s cylinders. That’s billions saved each year.

But try putting a 12-pack of spheres in your fridge. They’d roll around like billiard balls, taking up space and spilling onto the floor. Worse, when you pack spheres into a box, they fill only about 74% of the space. The rest are empty gaps. Not great for shipping hundreds of millions of cases across the world.

A spherical can is a dream on paper, but in reality, it’s chaos in your grocery bag. Imagine cracking open a rolling soda ball at a picnic—it’s more likely to escape than to quench your thirst.

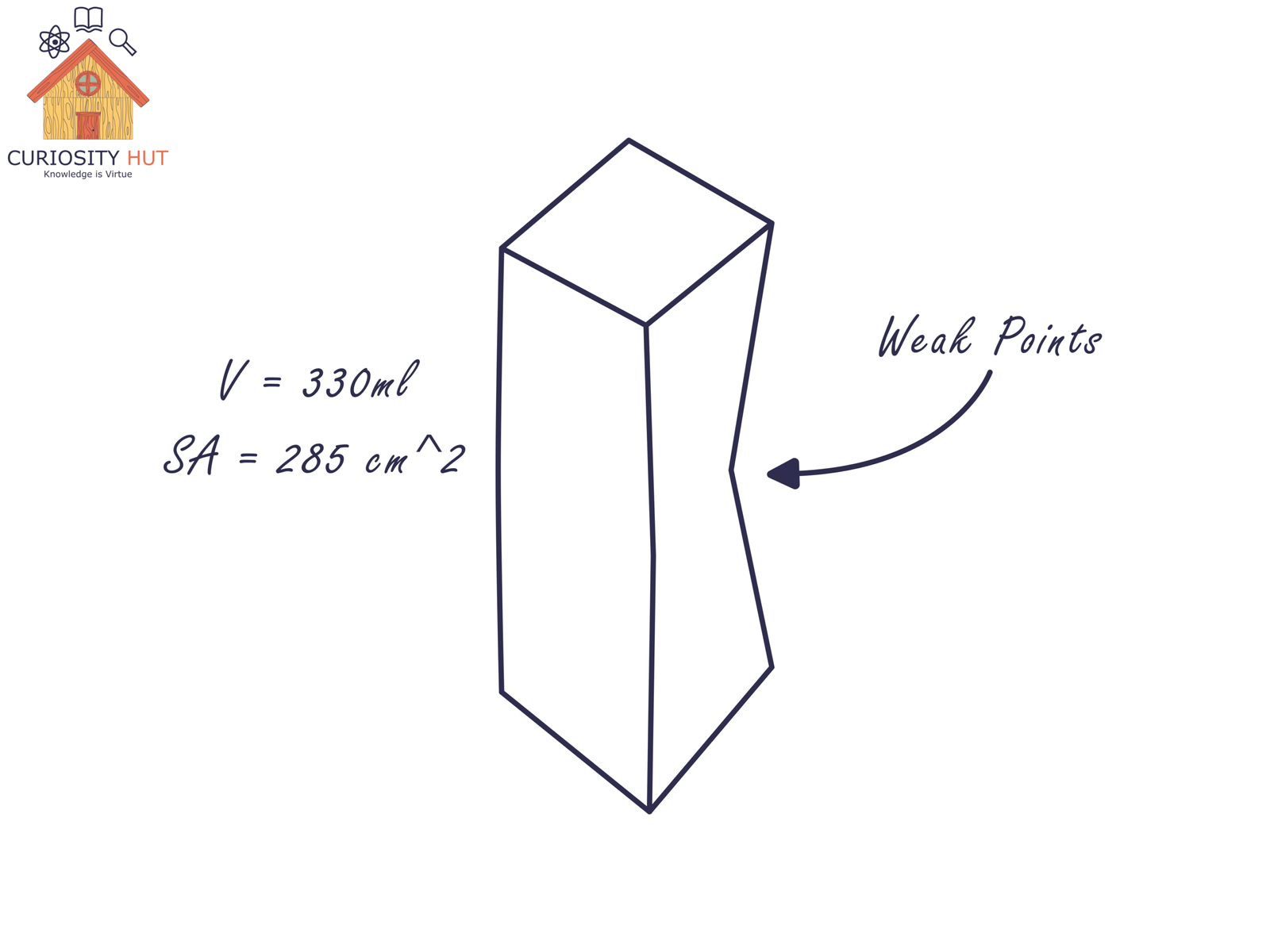

The Cube Catastrophe

If spheres are too slippery, what about cubes? On paper, cubes are perfect. They pack with 100% efficiency—stack them like Lego bricks and not a single gap is wasted. Shipping would be a dream. Your fridge would look like a Tetris masterpiece.

But soda isn’t only liquid—it’s pressurized liquid. Carbonation means billions of gas bubbles are pushing outwards at all times. Flat cube walls can’t take the pressure. They bulge, corners buckle, and before long, you’ve got a metallic pillow about to burst.

Then there’s the manufacturing nightmare. Aluminum starts as a flat sheet. Rolling it into a cylinder is simple: curl, seam, stamp, done. But folding it into a sharp, sealed cube corner? That’s like trying to gift-wrap a fizzy bomb. Expensive, slow, and ugly.

And let’s be honest—would you want to drink from a cube? Holding one would feel like sipping soda out of a brick. Not exactly thirst-quenching.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.

Why the Cylinder Wins

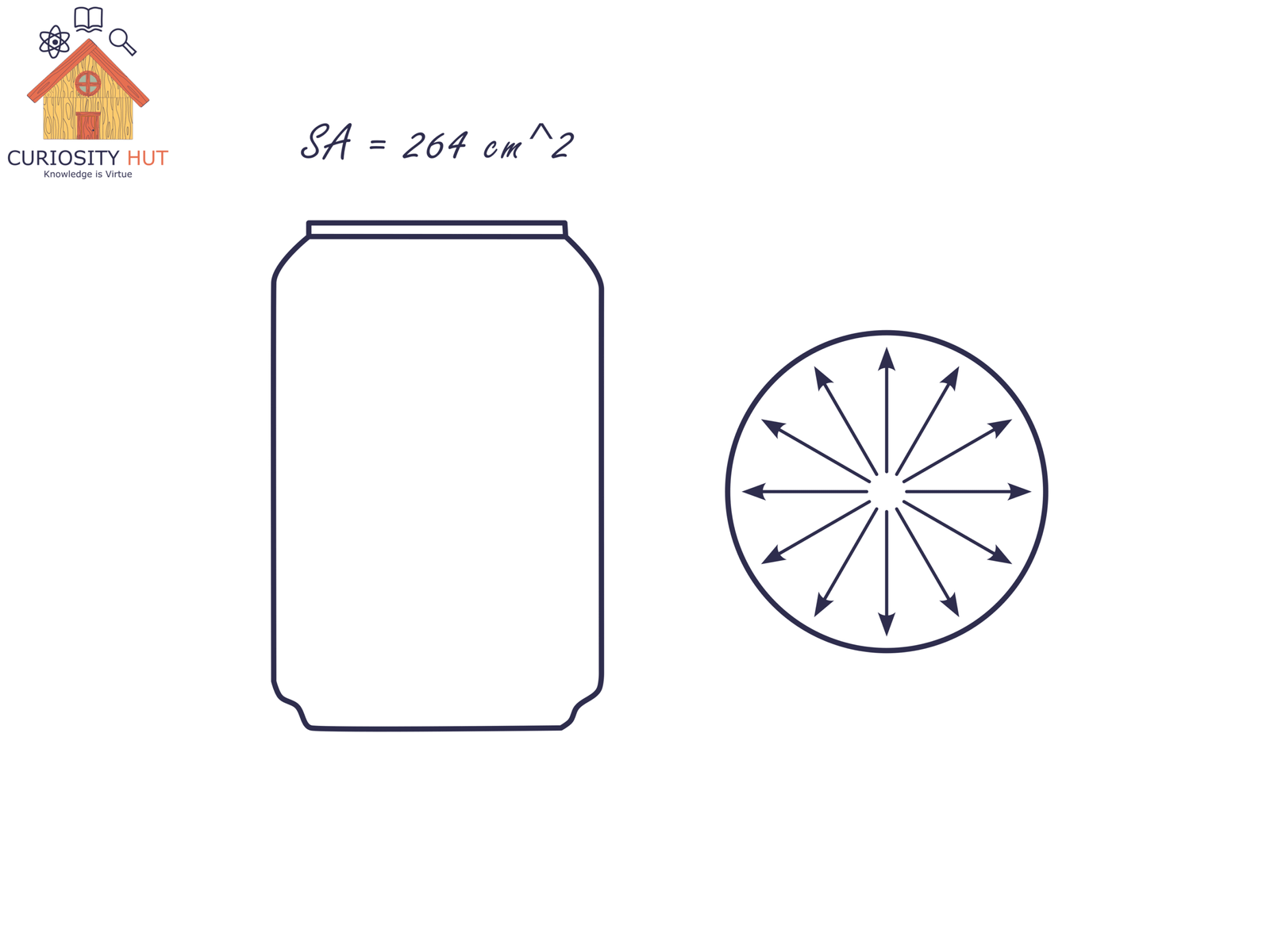

The cylinder doesn’t look flashy, but it’s a quiet genius. From the top, it behaves like a sphere—round, smooth, and great at spreading pressure evenly. From the side, it behaves like a cube—flat enough to stack without wasting much space. In fact, cylinders can pack with up to 91% efficiency. A sweet spot between the chaos of spheres (74%) and the perfection of cubes (100%).

For our standard 330 ml can, the surface area comes out to about 264 cm². Not as lean as a sphere’s 230, but far better than a cube’s 285. Multiply that by billions of cans, and you’re looking at mountains of aluminum saved.

But strength is where the cylinder shines. Carbonated drinks are tiny pressure vessels. Bubbles of carbon dioxide are always pushing outward. Cylinders spread that pressure evenly across their curved walls. A submarine hull or a gas pipeline works the same way. That’s why your soda can doesn’t bulge or burst (unless you shake it first).

Manufacturing seals the deal. Start with a flat aluminum sheet, roll it into a tube, press on a top and bottom, and you’ve got a can. Easy to extrude, easy to label, easy to pack into neat boxes. No weird corners, no runaway spheres. A design that’s cheap, strong, and human-hand friendly.

If engineers cared only about saving material, they’d have given you a soda sphere decades ago. But ergonomics, packing, and manufacturing win out. The cylinder is the Goldilocks solution: not perfect in theory, but unbeatable in practice.

If you look closer, a soda can isn’t a “perfect” cylinder at all. It’s full of quiet design hacks.

Start with the bottom. Notice how it’s domed inward a few centimeters, like the base of a wine bottle? A dome shape is far stronger under pressure than a flat plate. It prevents the can from bulging out and saves metal at the same time. Engineers call this doing more with less.

Now check the top. The lid is a little smaller in diameter than the body. That tiny reduction might not seem like much. But across billions of cans, it adds up to an enormous savings in aluminum. Smaller lid = less metal, faster sealing, fewer leaks.

And then there’s the tab. Early soda cans used a sharp pull-ring that detached completely. They littered beaches, cut feet, and ended up inside too many fish bellies. Today’s pull tab stays attached. It’s safer, cleaner, and as satisfying to snap open.

Tiny tweaks matter. Shaving even one gram of aluminum off each can saves about 280,000 tons of metal per year. That’s the weight of 1,400 fully-loaded jumbo jets—just from trimming a gram.

Your soda can isn’t yet another container. It’s a masterclass in small optimizations multiplied by hundreds of billions.

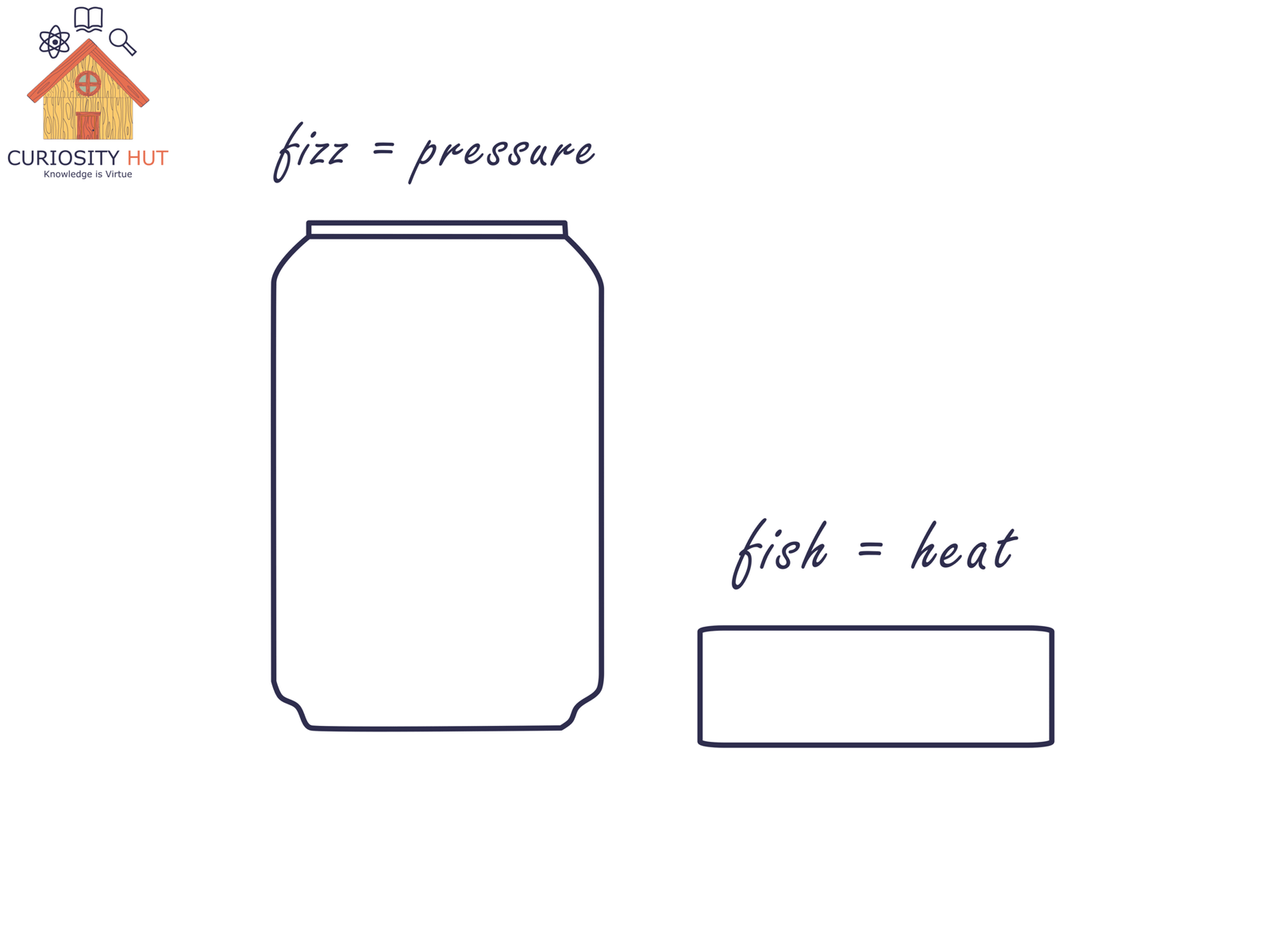

Why Tuna Cans Look Different

Not all cans face the same challenges. Take a look at a tuna can. It’s short, squat, and wide—almost the opposite of a soda can. Why? Because tuna doesn’t fizz. There’s no carbonation pressure trying to push the walls outward.

Instead, tuna cans are designed for heat. Before they reach the supermarket, the fish inside has to be sterilized. A squat, shallow can allows for quicker and more even heat penetration during processing. It ensures the outer layers will not overcook before the middle is safe to eat.

It’s the same material—thin sheets of aluminum or steel—but the optimization game is different. Soda cans are pressure athletes, built to withstand bubbles. Tuna cans are heat sprinters, built to cook fast and clean.

Even everyday packaging hides clever compromises, shaped not by fashion but by physics.

The Optimization Game

When engineers design containers, they’re playing a math puzzle. Given a set volume, how do you cut material use while keeping it strong, cheap, and practical?

For our 330 ml drink, the numbers look like this:

- Sphere: 230 cm² of surface area (the theoretical winner).

- Cube: 285 cm² (the wasteful loser).

- Cylinder: 264 cm² (the real-world compromise).

From the top, a cylinder is a sphere. From the side, it’s a cube. It borrows efficiency from both, while avoiding their worst flaws. Engineers can even tweak the height-to-width ratio to cut surface area further. That’s why cans are taller and narrower than you might expect. It’s a sweet spot that trims away hidden grams of aluminum.

The stakes are huge. Multiply every fraction of a millimeter by 280 billion cans a year, and you’re talking about millions shaved off production costs.

Optimization isn’t about perfection. It’s about balance—between geometry, physics, economics, and the way a can feels in your hand.

Therefore…

That soda can in your hand isn’t only packaging. It’s a triumph of geometry and engineering, refined over decades. Billions roll off assembly lines with near-perfect efficiency. Strong enough to hold pressure, light enough to save mountains of aluminum. Shaped just right to fit in your fridge—or your hand at a summer barbecue.

Therefore… the next time you crack a cold one open, remember you’re holding a tiny optimization puzzle.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.