From orbiting satellites to the phone in your pocket, the quiet choreography that pinpoints your position on Earth.

Navigation apps like Google Maps or Apple Maps have become invisible infrastructure. You use them to drive across town, but also when you’re sitting on your couch ordering takeout. The driver follows a glowing line on their phone, and you watch their icon creep closer to your door in real time. When you ride a Lime scooter, the app knows whether you’re on the road or the sidewalk. That level of precision is astonishing—and we barely notice it.

We don’t value this technology because we don’t understand it. GPS feels like software, or maybe magic. In reality, it’s a carefully choreographed system of satellites, signals, and geometry. In this post, we’ll unpack the basics of GPS and explain how your phone knows where you are, almost all the time, anywhere on Earth.

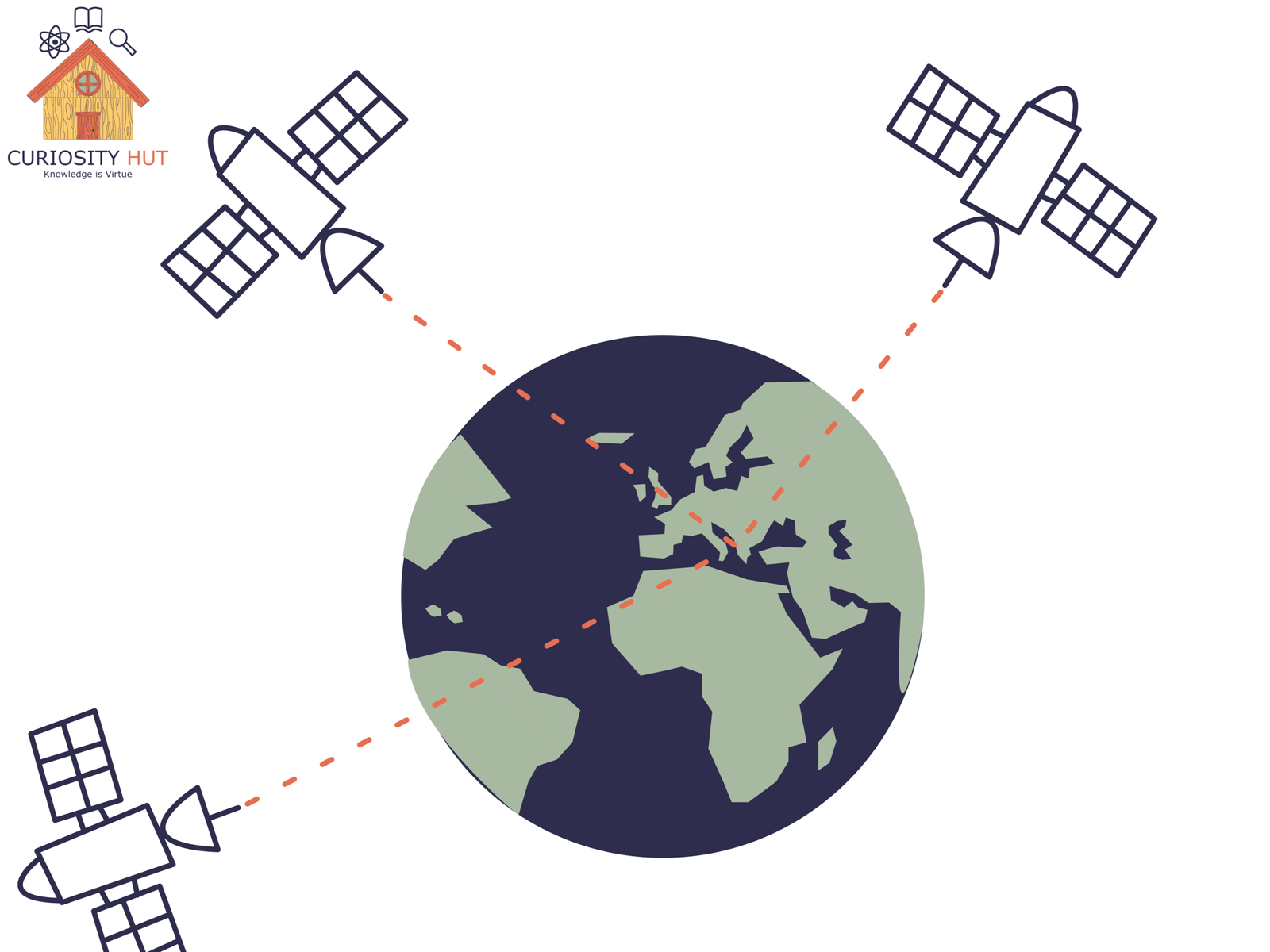

The Satellite System Above Your Head

GPS (Global Positioning System) began as a military project. The first satellites were launched by the U.S. Department of Defense in the late 1970s, and the system became fully operational in the mid-1990s. What started as a way to guide submarines and missiles quietly became a public utility for the entire planet.

A GPS satellite doesn’t see you. It has no camera, no map, no idea which way you’re facing. All it can do is broadcast a signal that says two things: where the satellite is, and exactly what time it is. Your phone listens and measures how long that signal takes to arrive. From that delay, it calculates distance—but not direction.

That single distance places you somewhere on a giant invisible sphere centered on the satellite. You could be north, south, above, or below. One satellite narrows things down, but it doesn’t tell you where you are. For that, you need more voices from space.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.

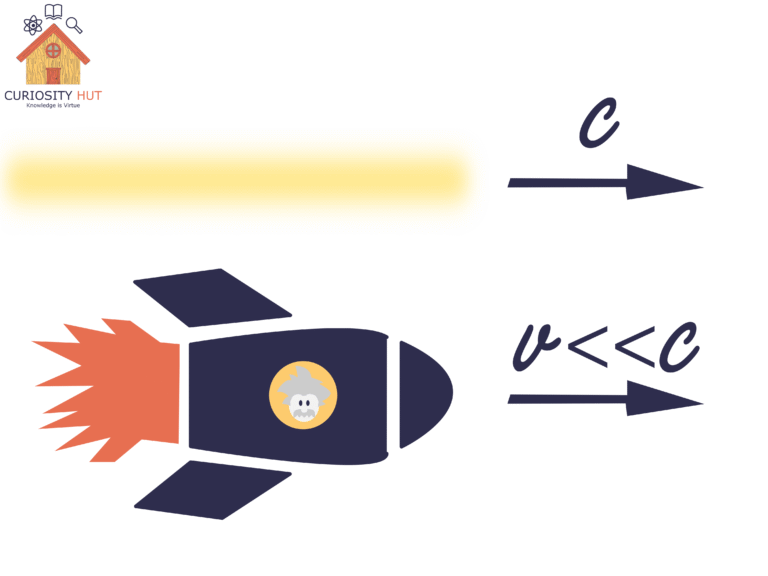

Measuring Distance at the Speed of Light

GPS signals are radio waves, which means they travel at the speed of light—about 300,000 kilometers per second. Each satellite constantly broadcasts the exact time it emits a signal. Your phone compares that timestamp to the moment the signal arrives. The difference between those two times is tiny, but it’s everything.

If a signal arrives 0.07 seconds after it was sent, that means it traveled roughly 21,000 kilometers. That number isn’t guessed or approximated. It’s calculated by multiplying time by a speed that physics has nailed down with unsettling precision. Your phone does this math in a fraction of a second, over and over, with multiple satellites at once.

That distance defines a sphere in space, with the satellite at its center and you somewhere on the surface. The problem is no longer “Where am I?” It’s “Where do these invisible spheres intersect?” GPS works because this geometry problem is solvable—but only if your clocks, signals, and calculations are absurdly precise.

Triangulation: Turning Distance into Location

To turn distance into position, GPS leans on geometry. The same kind you learned in school, just executed at orbital scale and relativistic speed.

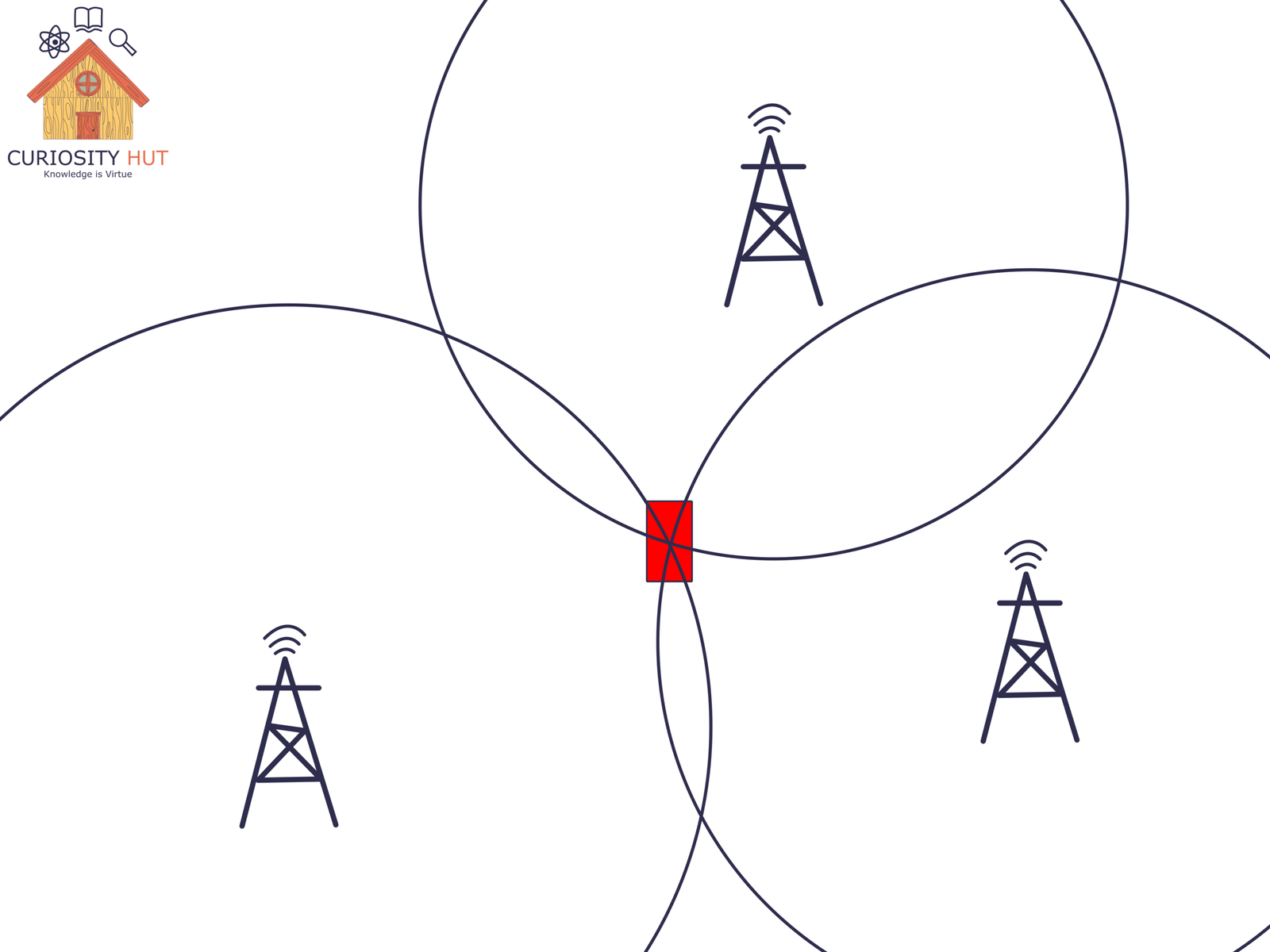

Imagine a flat, two-dimensional map. One satellite gives you a circle of possible locations, every point the same distance from the source. Add a second satellite, and you get two circles. They intersect at two points. Add a third, and only one intersection makes sense. In theory, three signals are enough to pinpoint your location.

In the real world, that neat solution breaks down. Your phone’s clock isn’t perfectly synchronized with the atomic clocks on the satellites, and even a tiny timing error explodes into kilometers of positional error. This is why GPS doesn’t stop at three satellites. A fourth signal lets the system solve not just for your position, but for time itself.

That extra satellite also unlocks altitude. GPS isn’t solving for latitude and longitude alone—it’s solving four variables at once: your position in three dimensions and the clock error in your device. Once time is corrected, height falls out of the math. The result is a three-dimensional fix that works whether you’re on a road, a bridge, or a hillside.

Why Altitude Is the Hard Part

Latitude and longitude behave nicely. Altitude does not.

Horizontally, satellites are spread across the sky, giving GPS strong geometric leverage. Vertically, everything is stacked. Most satellites are above you, not below, which makes height much harder to pin down. Small timing errors that barely affect your position on a map can translate into large errors in altitude. The signal is there, but it’s noisier, less stable, and easier to confuse.

Anyone who has driven through downtown Chicago knows this failure mode well. Take Lower Wacker Drive, and your GPS loses its mind. It knows you’re somewhere near the river, but it can’t tell whether you’re underground or cruising on the street above. From the satellite’s perspective, those two locations are almost indistinguishable.

This isn’t a bug so much as a limitation of geometry. GPS can measure distance with incredible precision, but resolving height requires cleaner signals, better timing, and often help from other systems closer to the ground.

Satellites Meet the Ground: How Your Phone Talks to the World

GPS isn’t just satellites floating in space. Your phone often relies on a network of antennas—cell towers, Wi-Fi hotspots, and other ground-based signals—to speed up and refine location fixes. This system, called Assisted GPS (A-GPS), helps your device lock onto your position faster, especially in cities crowded with tall buildings and signal reflections.

In urban areas, your phone is usually leaning on these terrestrial signals. That’s why your location snaps into place almost instantly. Out in the fields, deep in a forest, or anywhere with poor reception, your device has to rely purely on satellites. The fix still works, but it takes a bit longer, and the signals are more vulnerable to interference.

The takeaway: GPS is a hybrid system. Space gives you accuracy, but the ground gives you speed and reliability. Together, they make your phone’s blue dot feel like magic.

Knowing Where You Are in a Moving Universe

GPS works because space, time, and geometry line up in ways that almost feel miraculous. Atomic clocks in orbit, invisible spheres intersecting across thousands of kilometers, and antennas on the ground all conspire to tell your phone exactly where you are.

The next time you watch that little blue dot glide across your screen, remember: it’s not magic. It’s physics, math, and engineering working together, quietly measuring our world with astonishing precision. In that moment, you’re witnessing how the universe can locate itself—and you within it.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.