Einstein once admitted to a mistake so large he called it his “biggest blunder.” When he first wrote the equations of general relativity, scientists thought the universe should either expand or collapse. But the idea of a changing cosmos seemed impossible. He patched his math with a “cosmological constant,” a fudge factor to keep the universe still.

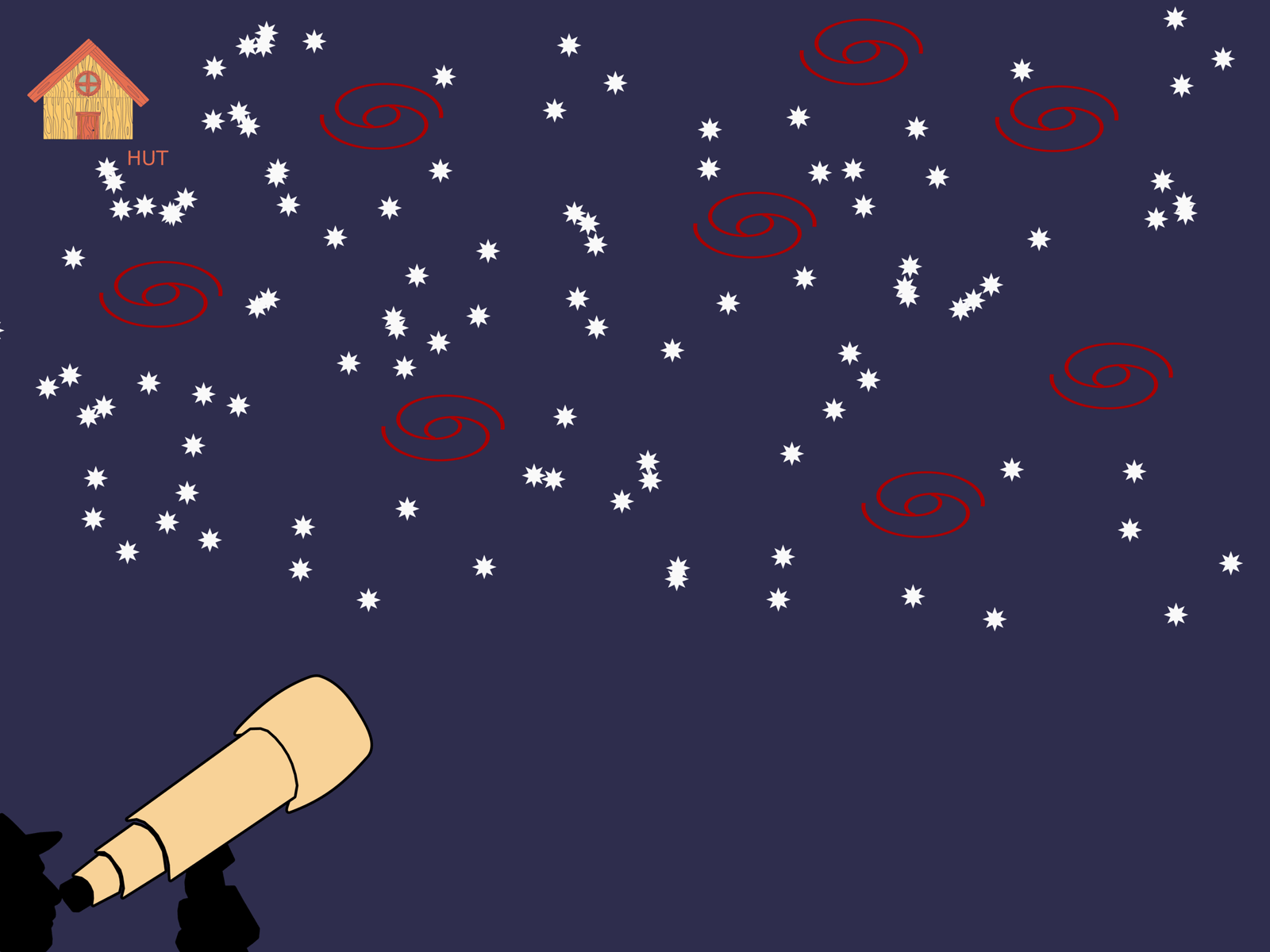

Then came Edwin Hubble. In the late 1920s, with the 100-inch telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory, Hubble found that galaxies were not standing still at all. They were racing away from us, and the farther they were, the faster they fled. It was undeniable evidence of an expanding universe.

Einstein was skeptical at first, but the data spoke louder than theory. He traveled to California, climbed the steps to Hubble’s observatory, and looked through the telescope himself. The sight forced him to abandon his static universe and concede that the cosmos was far stranger than he had imagined.

The Old Assumption of a Static Universe

For most of history, people imagined the universe as eternal and unchanging. Stars fixed themselves to the sky, shining forever. The cosmos felt solid, steady, and safe.

Even when telescopes revealed new details, the idea of a static universe held on. Why wouldn’t it? If the stars had always been there, why should anything change?

But there was a problem. If the universe is infinite and filled with stars, then the night sky should blaze with light. Every line of sight should end on a star. The heavens should be as bright as the surface of the Sun.

Instead, the sky is dark. This puzzle became known as Olbers’ paradox. It whispered that something about our picture of the universe was wrong.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.

The Language of Motion—Doppler and Redshift

Hubble couldn’t watch galaxies drift across the sky. They were too far, their motion too slow to see. Instead, he measured their light.

Light, like sound, travels in waves. And waves carry clues.

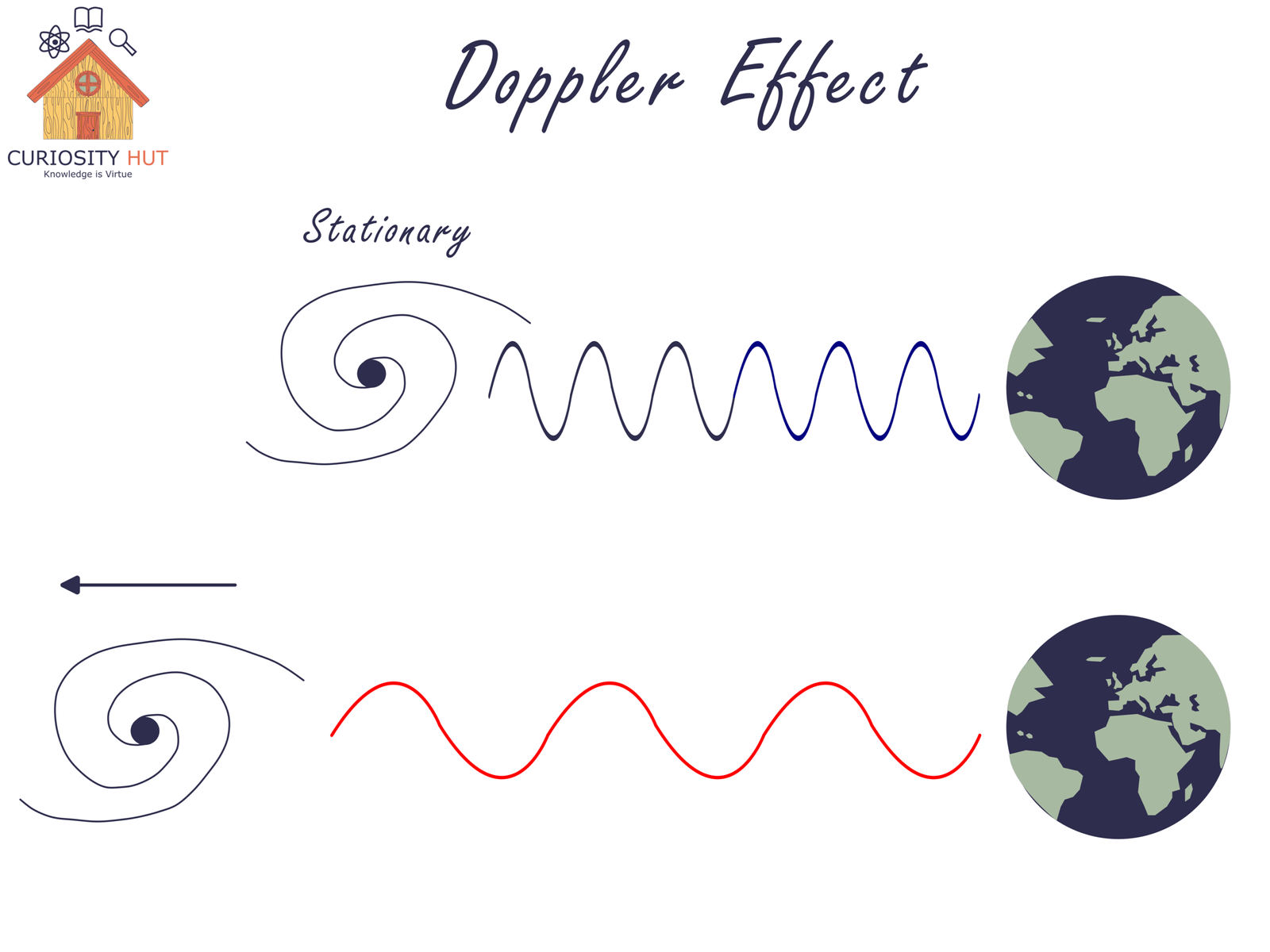

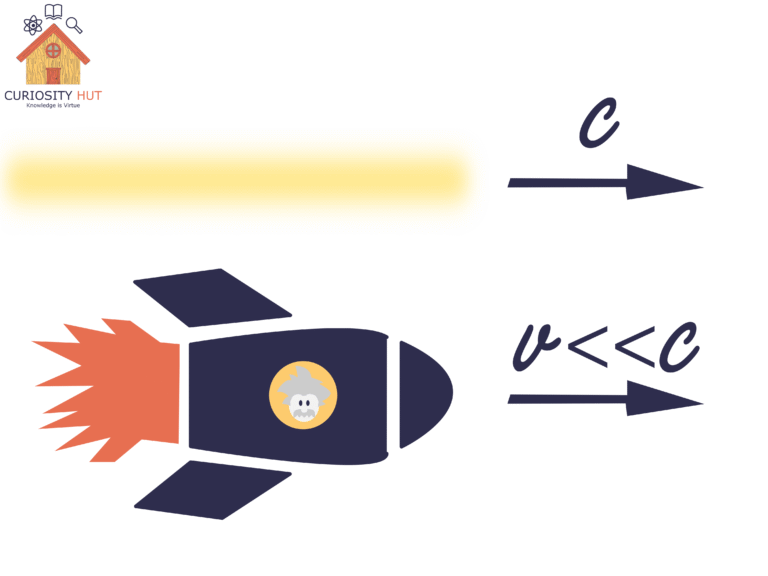

You already know this from sound. When an ambulance rushes toward you, the siren rises in pitch. As it passes and drives away, the pitch drops. The change happens because the sound waves are squeezed on approach and stretched as they recede. That everyday shift is called the Doppler effect.

Now swap sound waves for light waves. A galaxy moving toward us has its light squeezed into shorter wavelengths—it looks bluer. A galaxy moving away stretches its light into longer wavelengths—it looks redder. We call the shift toward red the redshift.

Astronomers can measure this effect with astonishing precision. By splitting a galaxy’s light into a rainbow spectrum, they look for the chemical fingerprints of hydrogen, helium, and other elements. Those fingerprints are always the same pattern. But in distant galaxies, they appear shifted—nudged toward red. The farther the galaxy, the greater the shift.

That was Hubble’s breakthrough. He wasn’t seeing that galaxies move. He was reading the hidden message carried in their light: the universe itself was expanding.

The Expanding Balloon

Redshift told Hubble something extraordinary: space itself was stretching. The galaxies weren’t like cars speeding down a highway. They were more like dots painted on a balloon as it inflates.

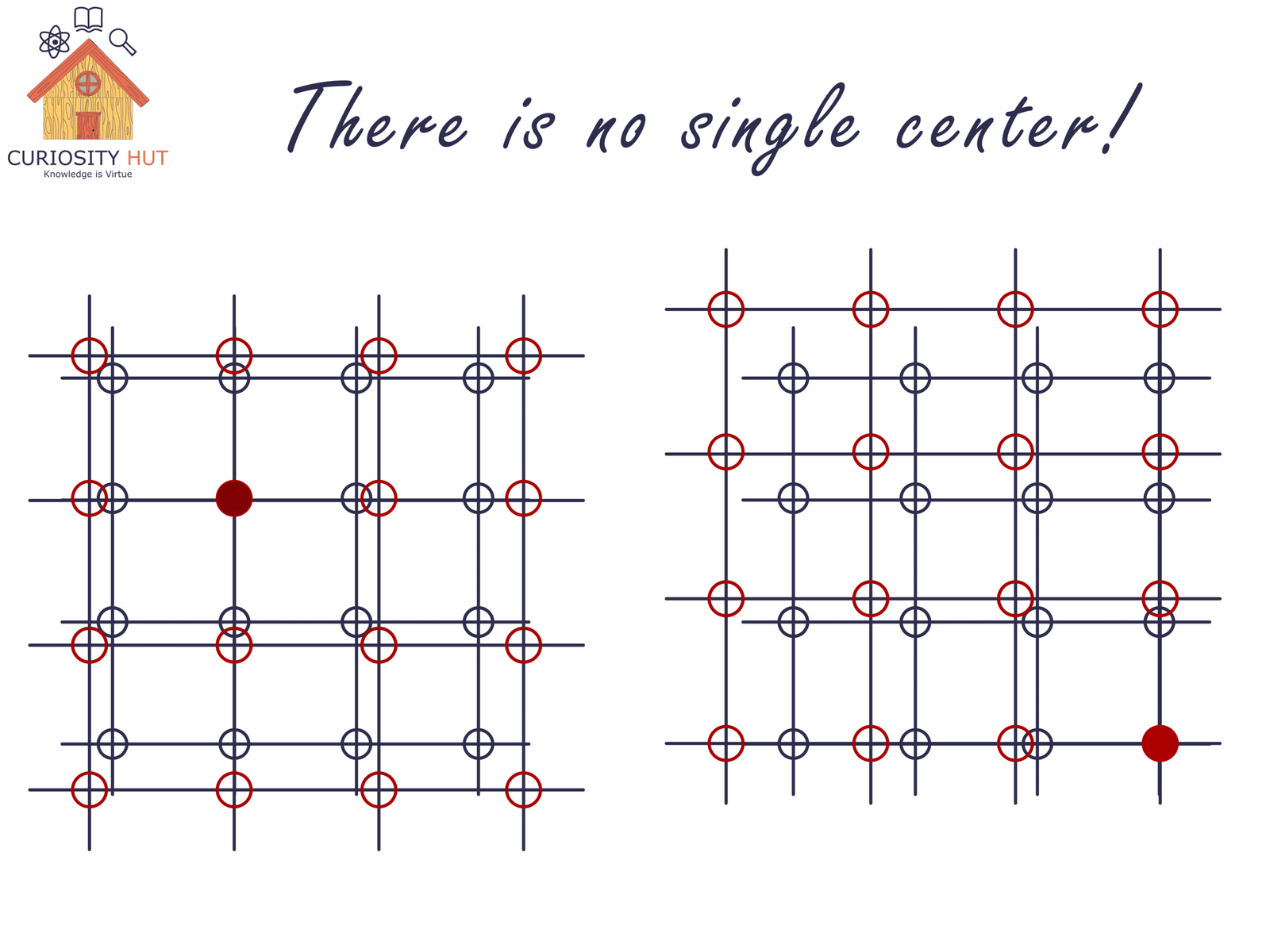

Blow up the balloon, and every dot moves away from every other dot. From the point of view of one dot, all the others seem to be receding. But there is no single “center” on the surface. Expansion happens everywhere at once.

This idea can feel slippery. Stephen Hawking explains it in A Brief History of Time with more depth, but you don’t need equations to picture it. Just think of that balloon. The galaxies aren’t flying through space—they’re being carried along as the space between them grows.

For a visual, see the figure I’ve added below. Notice how every point sees the same thing: the farther away another point is, the faster it seems to move away. That’s what Hubble discovered in the real universe.

The Echo of Creation

If the universe is expanding, it must once have been smaller, hotter, and denser. Run the clock backward, and everything converges. That idea led scientists to a daring thought: the universe began in a single explosive moment—the Big Bang.

For decades, this was a theory. Then, in 1965, two radio engineers, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, stumbled on a strange hiss of static. No matter where they pointed their antenna, the noise was there. They thought it was a problem with the equipment. They even cleaned out pigeon droppings from the dish, hoping to get rid of it. But the hiss remained.

It wasn’t noise. It was a signal. The faint glow of the newborn universe stretched into microwaves by billions of years of expansion. Astronomers call it the cosmic microwave background—the afterglow of creation itself.

This radiation bathes the cosmos. It fills every patch of sky, uniform yet laced with tiny ripples that seeded the galaxies we see today. It is, in a sense, the oldest light we can see—the universe whispering its origin story.

A Universe That Teaches

The universe is expanding. Galaxies drift apart, space itself stretches, and the faint glow of the Big Bang whispers across the cosmos. Hubble showed us that the sky is not fixed. The universe is alive with motion, change, and history.

Yet the story is also human. Einstein’s brilliance did not protect him from being challenged. Hubble’s careful observations corrected even the greatest mind of the age. Their encounter reminds us why science exists: not to defend ego, but to uncover truth.

We study, observe, and publish so that ideas can be tested, questioned, and refined. The universe does not care what anyone believes, and that is its gift. Its laws are impartial, its story vast, and its mysteries endless.

To look up at the night sky now is to see both the cosmic ballet of expanding galaxies and the human journey of curiosity, humility, and discovery.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.

[…] Here is an example from my blog (“How Do We Know the Universe Is Expanding?”): […]