A clear, no-nonsense guide to the chemistry, physics, and quirks behind everyday power sources.

A battery quietly powers nearly everything you rely on. Most explanations never get past vague hand-waving. You can’t really understand phones, laptops, cars—or even a potato battery—without seeing what’s happening chemically. But a battery isn’t magic, and it only works because each part inside it plays a precise role. Once you see a battery as a controlled chemical struggle, the whole story clicks into place.

Inside a Battery: The Cast of Characters

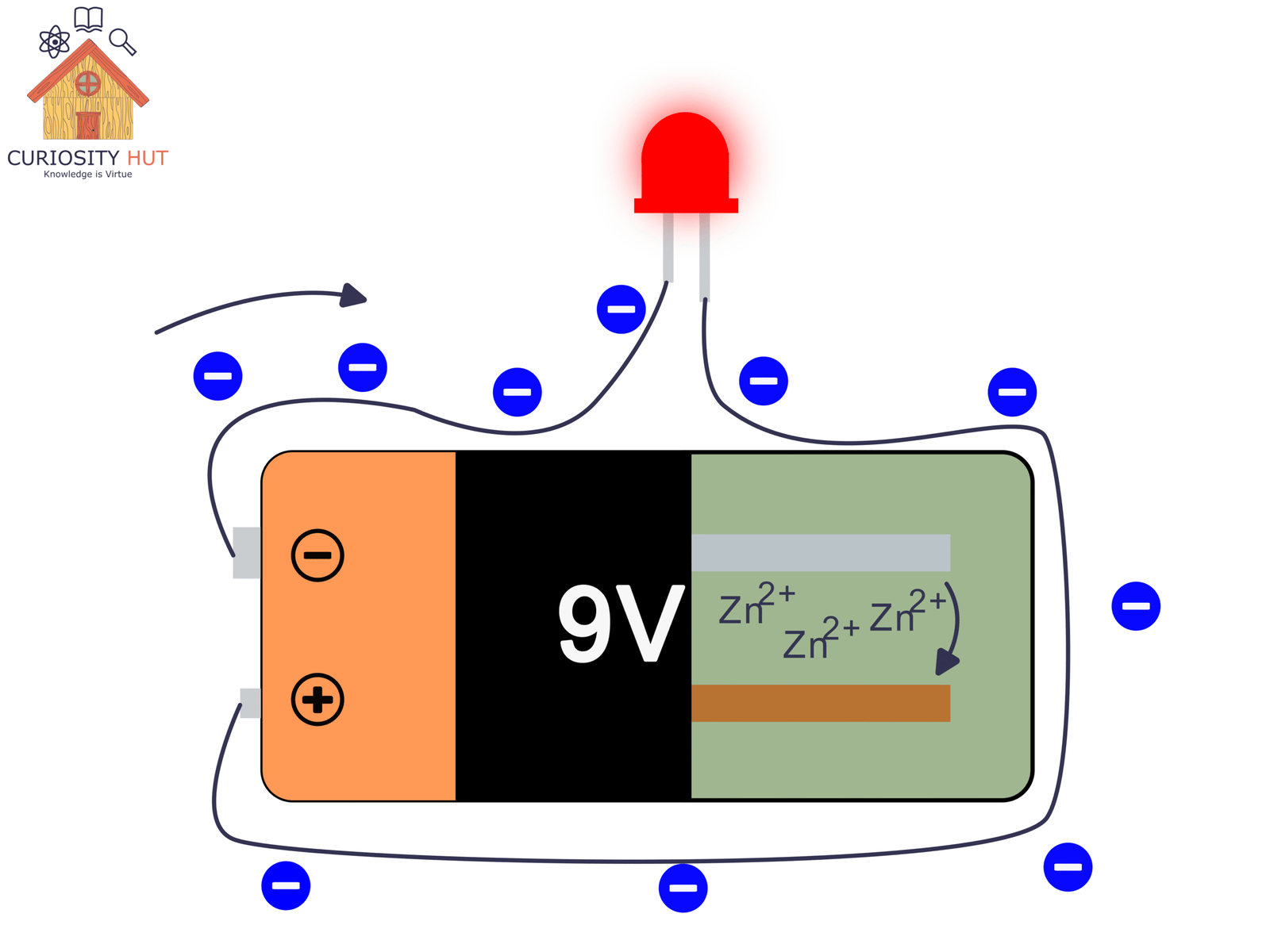

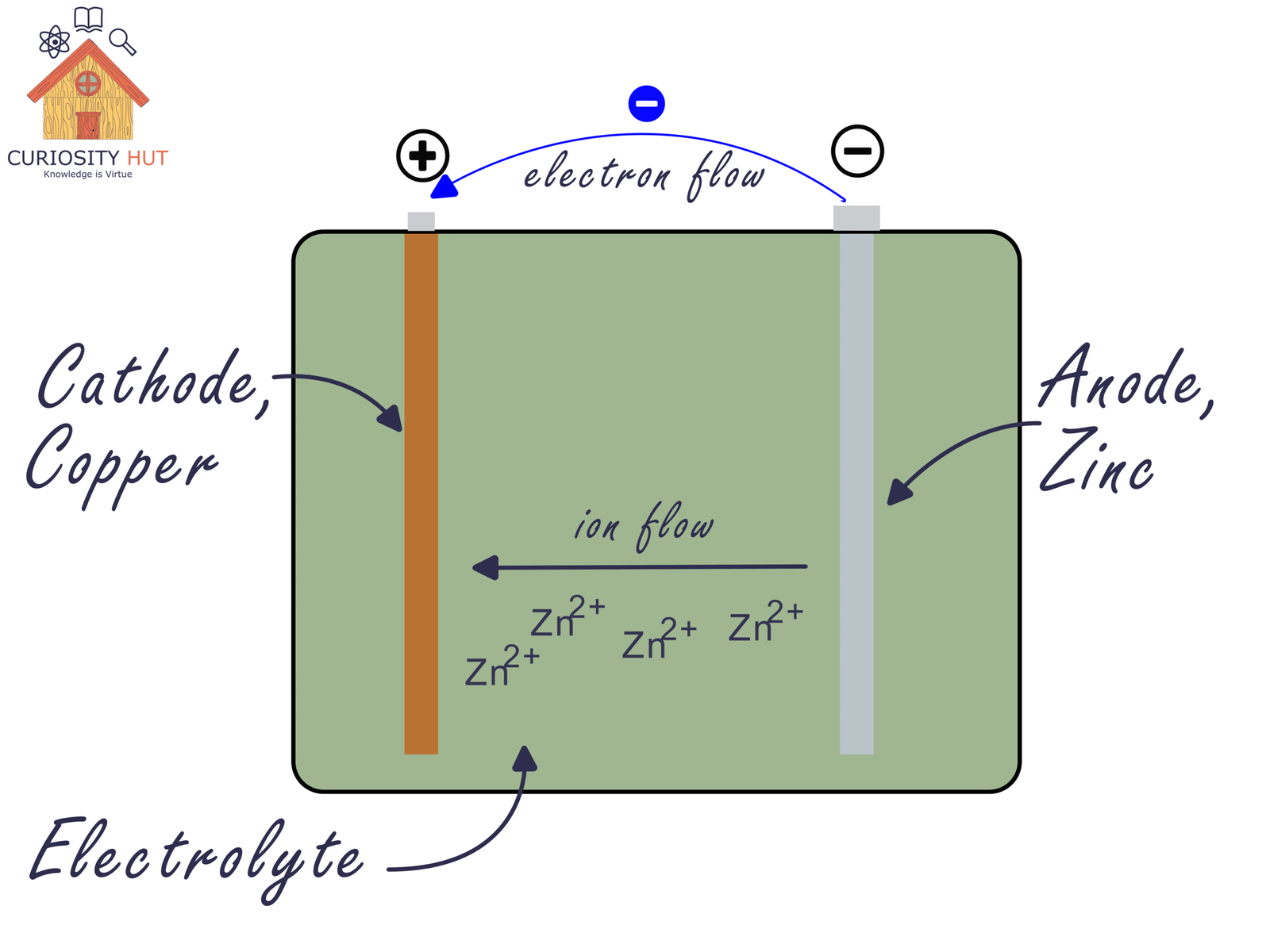

Every battery has three essential players:

The anode, a material that easily gives up electrons (zinc is a classic). That is the negative pole.

The cathode, a material that accepts electrons (often copper or copper-based compounds). That is the positive pole.

The electrolyte, a liquid or paste that lets ions—not electrons—move inside the battery.

Ions are simply charged atoms or molecules. They drift through the electrolyte to keep the battery balanced while electrons travel through the external circuit. A separator keeps the electrodes from touching, so the reaction doesn’t explode in a single useless burst. Put together, these parts create a tiny arena where chemistry produces an electric current.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.

Why Zinc and Copper?

Zinc and copper make a great pair because they strongly disagree about electrons.

Zinc gives them up easily; copper wants to take them. That difference—called reduction potential—creates a natural push. Whenever you provide a path, electrons flow from zinc to copper. That push is the cell’s voltage. It’s simply the chemistry of the metals trying to move toward stability.

This is why zinc–copper setups show up in classic demos. They’re predictable, visible, and make the chemistry easy to follow, though many other metal pairs work too.

The Electrolyte: Ion Highway

When zinc oxidises, its atoms become Zn²⁺ ions and drift into the electrolyte. The 2+ means the atom lost two electrons. On the copper side, copper or copper compounds take in electrons and may release or absorb ions as part of their own reaction.

Electrons move through the wire.

Ions move through the electrolyte.

Both are required.

Without ion motion, charge would build up on one side, electron flow would choke, and the battery would stall instantly.

Electricity Basics (Just What We Need)

- Electrons = tiny charged particles that move through metals.

- Current = their collective drift.

- Voltage = the push behind that drift.

- Resistance = anything that slows them down.

A battery only works when the circuit is closed. Electrons leave the anode, do some job in your device, and return to the cathode while ions shift internally to keep the balance.

How Batteries Store Energy

A battery stores chemical potential—not electricity. When the reactive materials are kept apart, they hold tension: zinc wants to oxidise, the cathode wants to reduce, but the separator and electrolyte hold the system in check.

Connect a circuit, and you give that tension an escape. The reaction begins, electrons flow, ions migrate, and the cell slowly moves toward a lower-energy, more stable state. That controlled move toward stability is the power you use.

Why Batteries Run Out

Batteries don’t run out because electrons disappear, since electrons cycle. What actually runs out is the chemical imbalance that drives them.

- Zinc atoms turn into ions and leave the anode eaten away.

- Cathode materials change as they accept electrons.

- By-products accumulate and make ion movement harder.

Eventually the voltage drops so low that your device can’t run. The battery isn’t empty of electrons—it’s empty of usable chemistry.

How Rechargeable Batteries Work

Rechargeable cells reverse their own chemistry.

Plug them in, and an external power source pushes electrons back where they started; ions migrate the opposite way through the electrolyte. The chemical tension resets.

But the process is imperfect. Each cycle slightly wears down the electrodes and electrolyte, so over time, the battery holds less energy—like refilling a bucket that slowly develops leaks.

How Temperature Affects Batteries

Temperature changes how quickly ions can move:

- Cold slows ions and raises internal resistance → battery feels weak.

- Heat accelerates reactions, including unwanted ones → battery ages faster.

Batteries are happiest at moderate temperatures—neither frozen nor cooking.

Why the Last 1% Lasts Longer

Batteries don’t discharge evenly. Midway through, the voltage drops quickly. Near the end, the remaining chemistry produces current more slowly but steadily, so that “1%” can linger.

It’s like taking the last slow sips from a water bottle—less pressure, but still something left.

A Simple Potato Battery

You can see all these principles with a potato, a zinc nail, and a copper coin:

- Insert the metals into the potato.

- Connect wires to an LED or voltmeter.

- Zinc oxidises and releases electrons.

- Ions move through the potato; electrons flow through the wire.

- The LED lights or the voltmeter jumps.

Even a potato can become a tiny chemical engine.

Batteries in a Nutshell

A battery is a controlled chemical reaction that pushes electrons through a circuit.

Electrodes react, ions move, electrons flow, and energy is stored as chemical tension.

Batteries run out when their chemistry settles, can be recharged by reversing reactions, and behave differently with temperature. Even simple demos reveal the same principles powering your phone or laptop.

Understanding how batteries work makes the devices around us feel far less mysterious—and reveals the elegant chemistry running quietly inside them.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.