The Simple Physics Behind the World’s Fastest Communication System

You are reading this article because of fiber optics. Most of us know they exist, and we know they deliver fast internet. Yet very few people know what they actually are or how they move information. Search for an explanation and you’ll often get something like this:

“Fiber optics work by transmitting data as pulses of light through thin strands of glass or plastic. Data is converted into light signals, which then travel down the fiber via total internal reflection, bouncing off the core’s cladding layer. At the other end, a receiver converts the light pulses back into electrical signals that a computer can understand.”

It sounds neat, but it explains almost nothing. It gestures at “pulses of light” and “bouncing,” then quietly backs out of the room. Most articles and videos do the same. They rely on phrases that look scientific but skip the part you actually want to understand: how light stays inside a hair-thin strand of glass, and how engineers squeeze entire worlds of data into those flashes.

This article takes you inside the cable. First, the physical fiber, then the physics that keep light trapped inside it, then the clever encoding tricks that turn beams of light into global communication. All of it in simple terms.

Let’s start unraveling it.

What a Fiber Really Is

Imagine a fishing line stretched across a room. Shrink it until it’s thinner than a human hair. That’s the scale of a single optical fiber. Despite its delicate appearance, the core is made from extraordinarily pure glass—much cleaner than the stuff in windows or bottles—and that purity lets light travel long distances without fading.

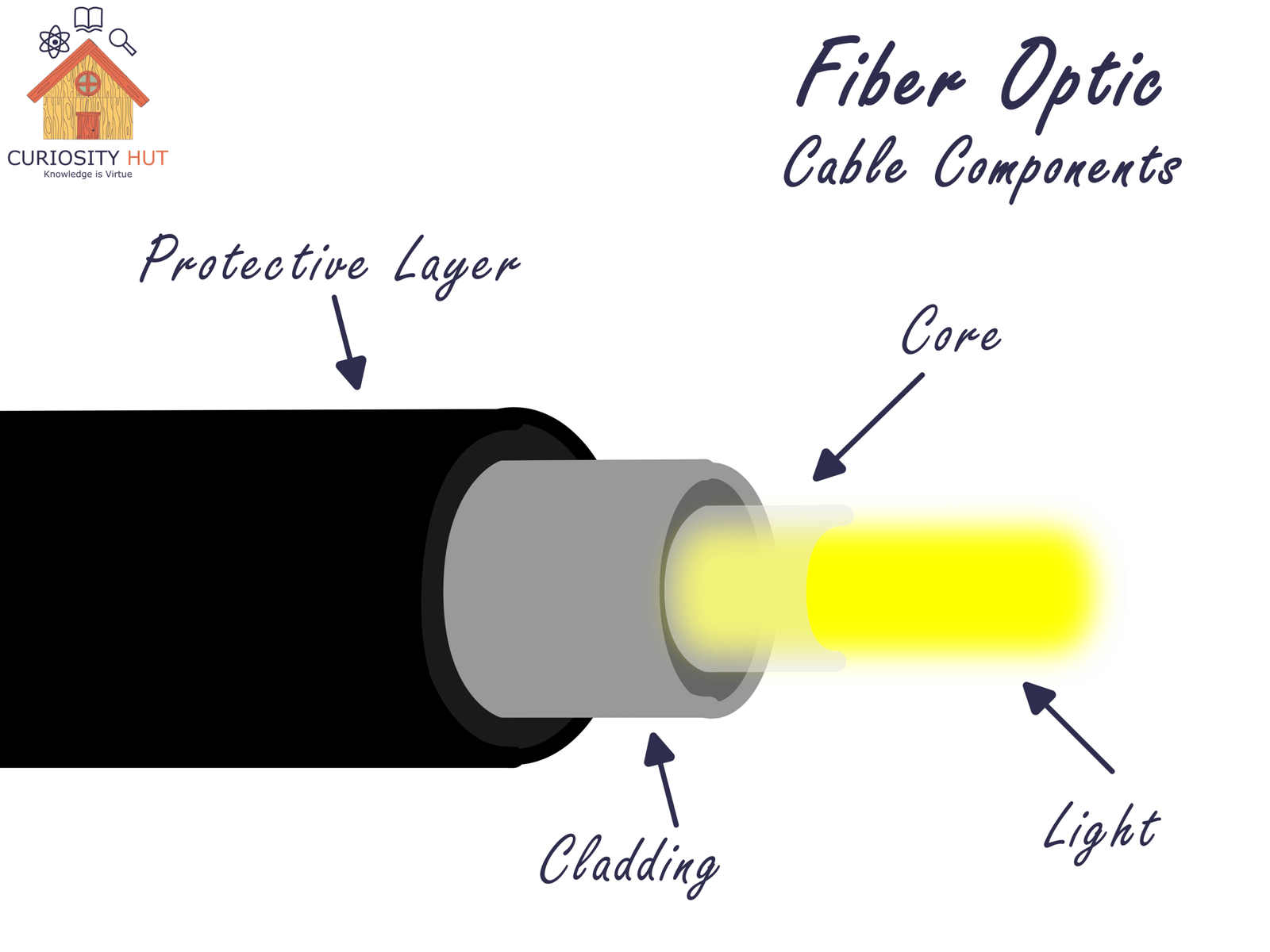

Wrapped around this core is the cladding, a layer of glass or plastic designed to keep the light from spilling out. How it does that will make perfect sense once we talk about refractive index in the next section. Finally, the entire strand is covered by a protective jacket, usually plastic, which shields the glass from bends, moisture, and everyday abuse.

The core carries the light. The cladding keeps it contained. The protective layer keeps the whole structure alive in the real world.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.

How Light Stays Inside the Fiber

Light moves startlingly fast—about 300,000 kilometers per second in a vacuum. Fast enough to go to the Moon and back in under two seconds. Inside materials, though, light slows down. And how much it slows down depends on the material itself.

That slowdown is captured by a simple number called the refractive index. It’s just the ratio between the speed of light in a vacuum and the speed of light in whatever material the light is entering. Pure glass has one refractive index, plastic has another, and air has another. When light crosses from one material into another, it bends. That bending is refraction.

The deeper physics behind why refraction happens could fill a chapter—and Feynman already did, in lectures you can find online for free—so we’ll stick to the essentials here.

What matters for fiber optics is this:

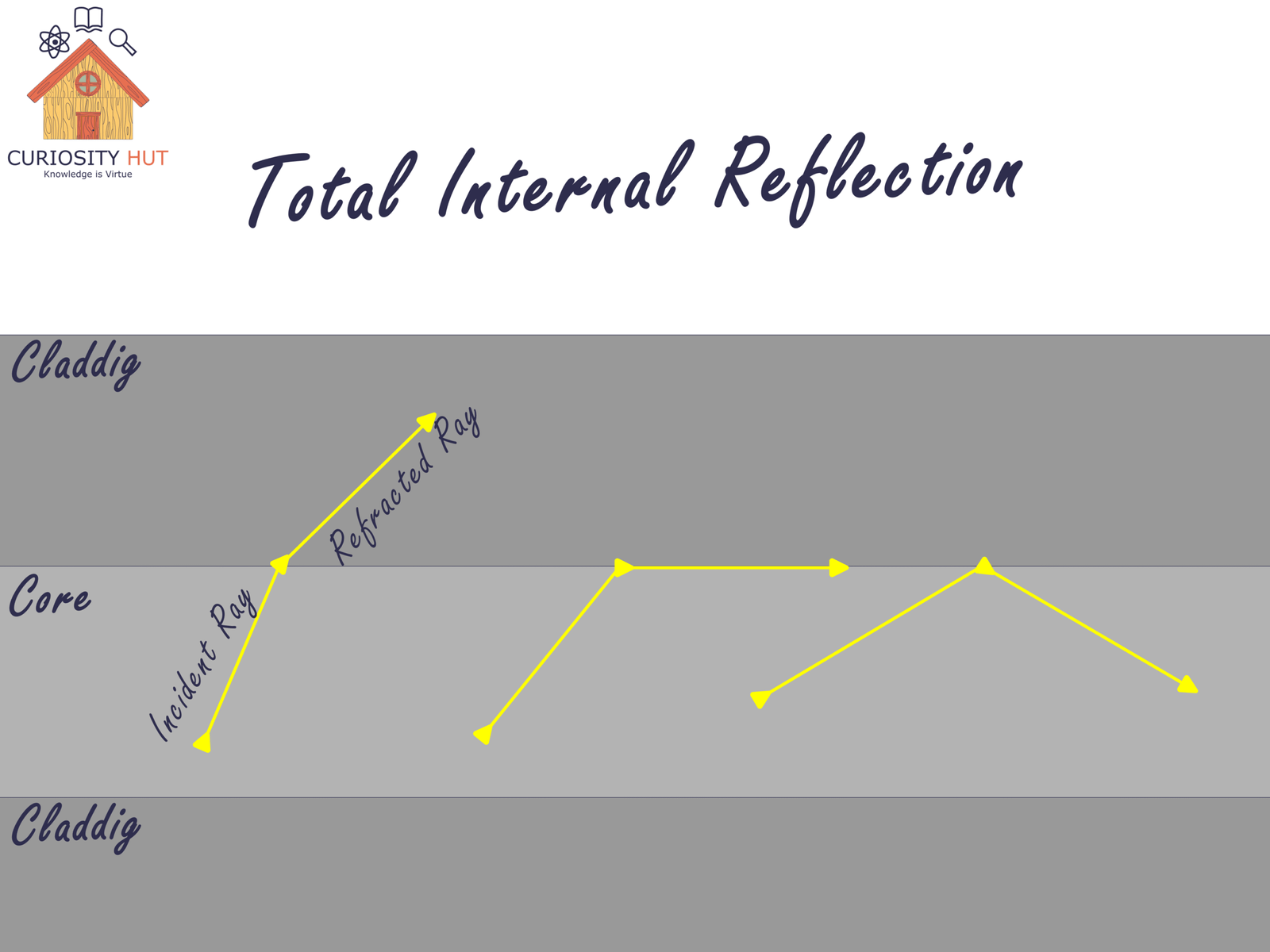

When light hits the boundary between two materials at a shallow enough angle, it bends.

But when it hits at a steep angle, something special happens. The light doesn’t escape at all. Instead, it reflects completely back into the material it came from. This is called total internal reflection.

Fiber optics are built to make this happen over and over. The core is made of very pure glass with a slightly higher refractive index. The cladding around it has a slightly lower one. So when light enters the core at a steep angle, every attempt to escape is blocked. It keeps reflecting, zig-zagging down the length of the fiber. The angle is so steep that the path is almost straight, and the light can travel kilometers with very little loss.

How Light Becomes Information

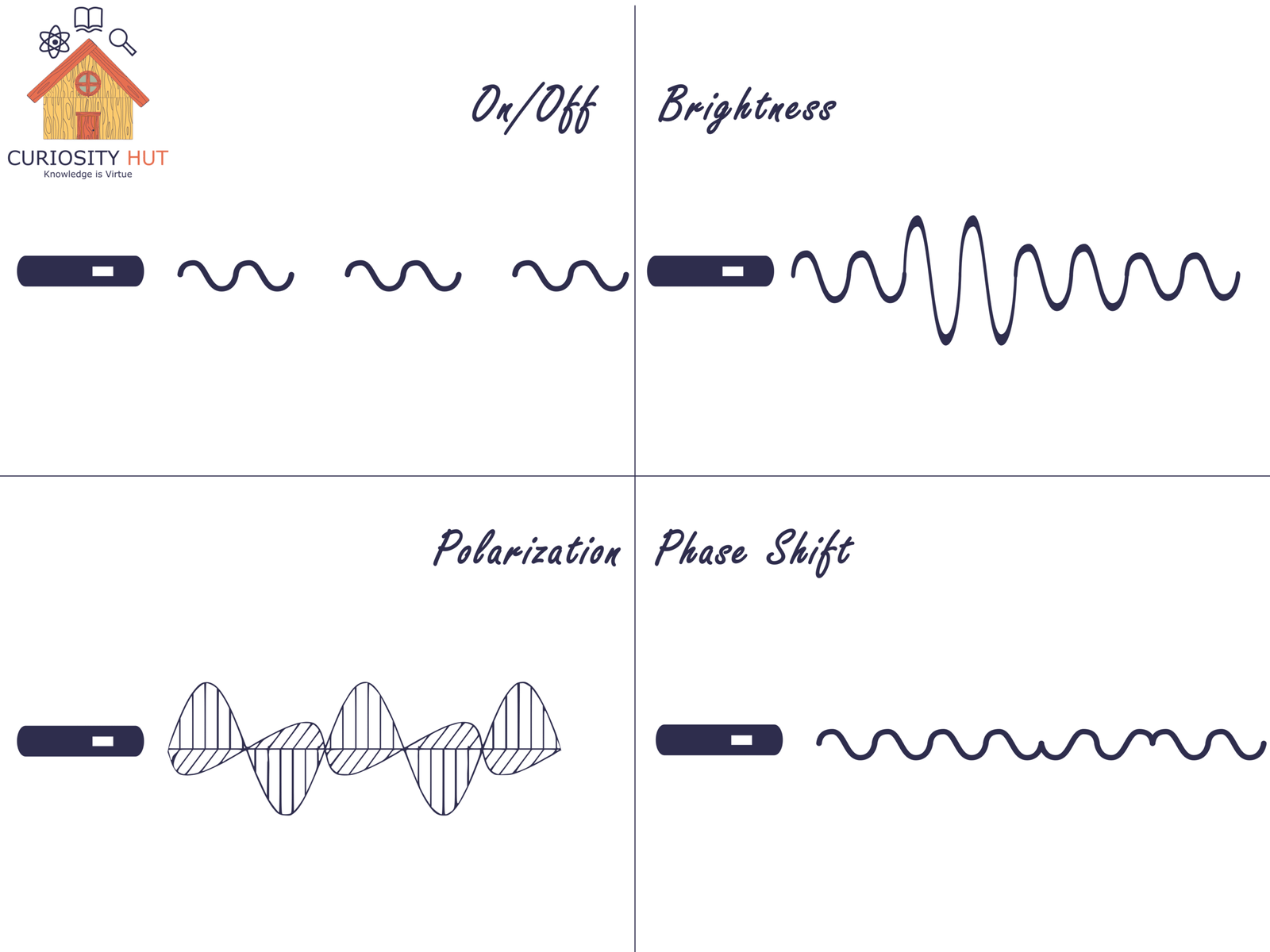

Once you’ve trapped light inside a fiber, the next question is the juicy one: how do you turn that beam into meaning? The simplest method looks a lot like Morse code. You switch the light on and off. In the digital world, that’s called binary—just 1s and 0s. Computers know how to take long strings of those pulses and turn them into text, images, videos, or whatever else we ask of them. How they make sense of binary is a story for another day.

But plain on/off signaling doesn’t take you very far. To send data faster, engineers add extra layers of nuance to the light. You can vary the brightness so that different intensity levels represent different bits. You can change the color—different wavelengths carry different streams of information at the same time.

You can also play with the orientation of the light wave, which is called polarization; think of it as the direction the light waves vibrate, like a very fast, invisible guitar string. And you can shift the phase, which is the light wave’s position in its cycle—essentially deciding whether the wave starts its “wiggle” a little earlier or later. Each of these tricks gives you more ways to encode what is ultimately still 1 and 0.

Once you combine these methods, even a single fiber can carry astonishing amounts of information, all racing through that hair-thin thread at nearly the speed of light.

Taking It to the Next Level

Once you’ve squeezed every bit you can out of a single beam of light—brightness, color, polarization, phase—you still want more. This is where engineering gets bold.

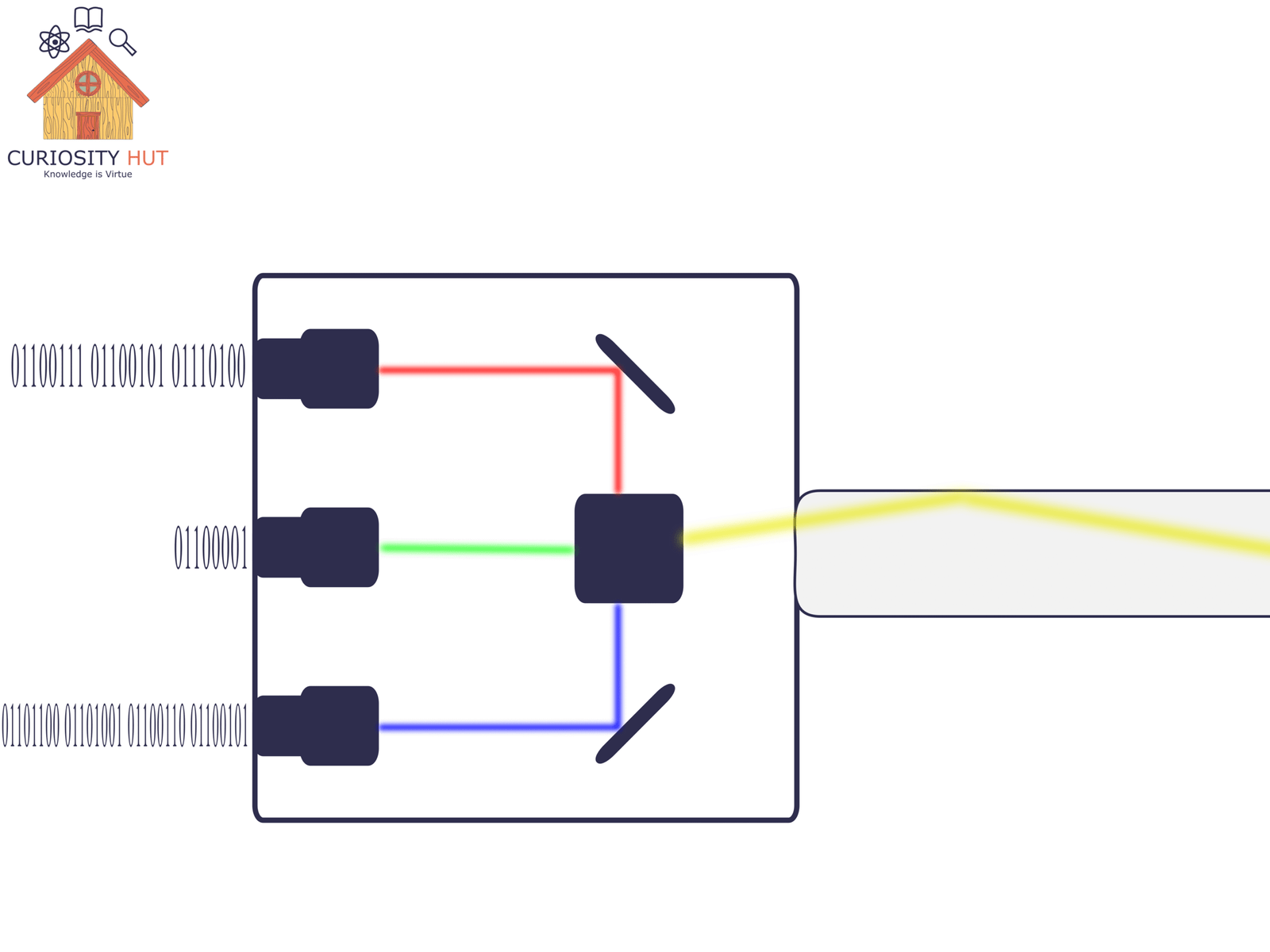

One approach is multiplexing, which is a fancy word for sending several streams of information through the same fiber at the same time. The easiest version uses different colors of light. Each color behaves like its own independent lane on a highway. If you shine red, green, and blue light down the same fiber—each carrying its own data—you’ve just tripled your capacity without adding any new cables. Modern systems use dozens of colors, each separated by tiny differences in wavelength, all racing side by side.

But capacity isn’t just about color. It’s also about how the fiber itself handles the path that light takes. That leads to the distinction between single-mode and multimode fibers.

In single-mode, the core is so thin that light can only take one clean, almost straight path. This keeps the signal sharp over long distances—perfect for undersea cables and communication lines that stretch across countries. In multimode, the core is wider, so the light can travel in several different zig-zag patterns at once. That makes the equipment cheaper and easier to use, which is why multimode fibers show up in data centers and buildings where links are short.

Put them together—better encoding, multiple colors, clever control of light paths—and the same glass strand becomes a monster communication channel. A cable the width of your thumb can hold hundreds of these fibers, each packed with many wavelengths, each wavelength packed with its own encoded torrent of binary. The engineering doesn’t just scale; it compounds.

Keeping the Signal Alive

Even with perfect glass and clever encoding, light still loses strength as it travels. Over a few kilometers, that’s fine. Over an ocean, it’s hopeless. To keep the signal alive, long-distance cables use amplifiers and repeaters spaced along the route.

An amplifier boosts the light directly—no need to turn it back into electrical signals. A repeater goes further: it converts the light to electricity, cleans up the data, and sends out a fresh beam. Modern systems rely mostly on amplifiers because they’re faster and simpler, but both exist for the same reason. Light, fast as it is, needs a little help on a very long journey.

With those boosts in place, a pulse of light that starts on one continent can reach another with its information intact.

Why Fiber Dominates — And Why It Matters

When you put everything together—the purity of the glass, the clever trapping of light, the rich encoding tricks, the multiplexed colors, the single-mode highways, the amplifiers humming deep under the sea—you get a communication system with almost absurd strengths. Fiber carries more data, loses less signal, shrugs off electrical noise, and scales in ways copper wires never could. A bundle of strands thinner than a shoelace can move the world’s conversations with room to spare.

Once you see the details, it stops feeling like magic. A fiber is just a carefully built path for light, and light is simply being nudged, steered, and patterned until it tells a story. That tiny glass thread under your street—one hair in a vast global braid—is the reason information can leap across the planet in the blink of an eye.

And now you know how it actually works.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.