Disclaimer: This post contains affiliate links to Bookshop.org. If you buy through these links, I earn a small commission at no extra cost to you, while supporting indie bookstores and my work.

A fake headline spreads on social media: a miracle cure for cancer, a politician in a huge scandal, a secret “they” don’t want you to find out. It looks convincing, and it feels right. Soon, thousands of people have liked it, shared it, and believed it. We don’t fall for false stories because we’re foolish—we fall because our brains are wired for shortcuts. And those shortcuts once helped us survive, teaching us to trust patterns, stick to familiar beliefs, and make quick judgments—but in today’s world of algorithmic filter bubbles, the same shortcuts can mislead us.

Therefore, if we want to resist fake news and false beliefs, we need tools that slow us down. The scientific method, open debate, and the uncomfortable but necessary habit of testing our own assumptions.

What is Confirmation Bias?

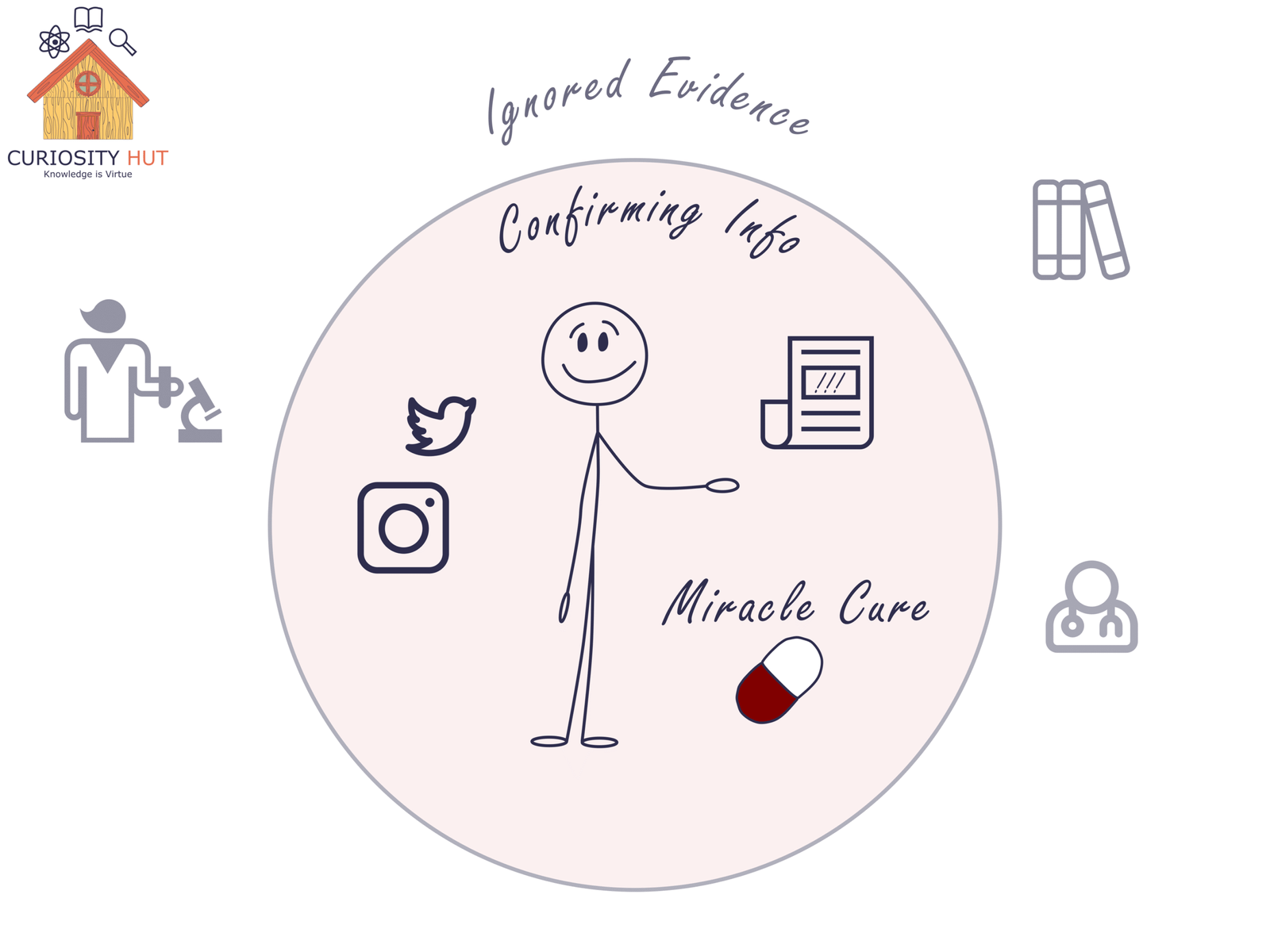

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, confirmation bias is “the tendency to process information by looking for, or interpreting, information that is consistent with one’s existing beliefs.” Put simply, it’s our brain’s habit of paying attention to what proves us right and tuning out what proves us wrong.

Confirmation Bias it’s our brain’s habit of paying attention to what proves us right and tuning out what proves us wrong.

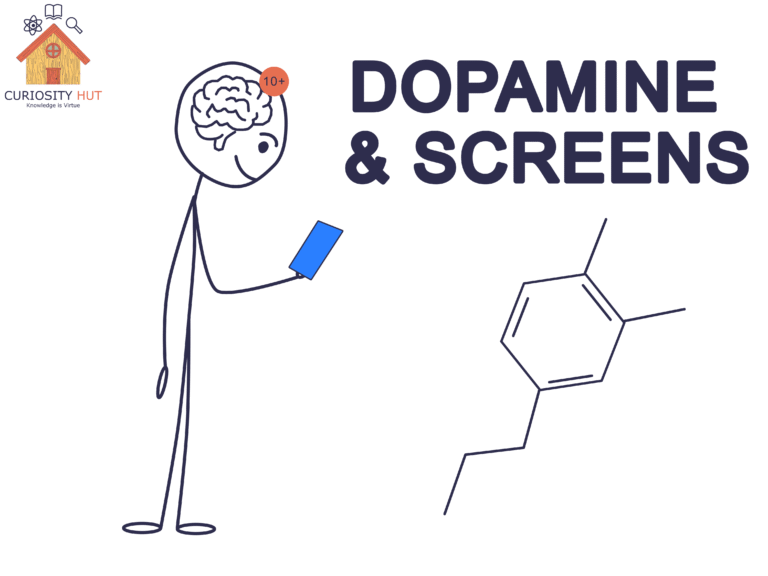

It doesn’t just happen in arguments with strangers online. It happens quietly, invisibly, in all of us. We scroll past articles that challenge our views, engage more with ones that agree with us, and remember confirming details while forgetting contradictions. We even feel a jolt of satisfaction—almost like a reward—when a piece of news validates what we already believe.

Psychologists point to several signs that confirmation bias is at work:

- Seeking out only information that supports your beliefs and dismissing what doesn’t.

- Looking for evidence to confirm your assumptions rather than weighing all the evidence.

- Leaning on stereotypes or personal biases when interpreting information.

- Remembering facts that agree with you while conveniently forgetting the rest.

- Feeling strong emotions toward confirming evidence, but remaining indifferent toward conflicting evidence.

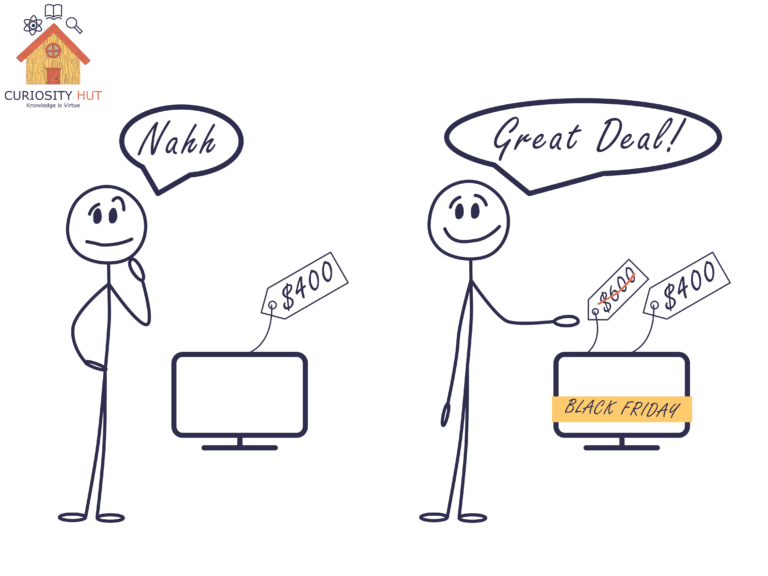

The reason it feels so convincing is that confirmation bias doesn’t feel like bias—it feels like truth. Our brains evolved to value patterns and consistency. Any evidence that fits our worldview slips in easily. But contradictions feel uncomfortable, even threatening. That discomfort is why we double down when confronted with facts that oppose our beliefs.

And here’s the crucial part: confirmation bias isn’t a flaw unique to “other people.” It’s universal. We’re all vulnerable, whether we’re scientists, doctors, or casual social media users. The difference lies in whether we recognize it and build habits to resist it.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.

Why We Fall For It: Fast and Slow Thinking

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman, in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, explains why confirmation bias is so hard to escape. Our brains run on two modes of thought: System 1 and System 2.

System 1 is fast, automatic, and intuitive. It’s the part of the mind that jumps to conclusions, finishes other people’s sentences, and instantly recognizes a face in a crowd. This system is great for survival—if you hear a rustle in the bushes, you don’t stop to calculate probabilities; you assume it’s a tiger and run.

System 2 is slow, deliberate, and rational. It’s what we use to work through a math problem, plan an argument, or check whether a claim actually makes sense. System 2 can question System 1, but it takes effort and energy. Most of the time, we let it nap.

Here’s where confirmation bias sneaks in. System 1 gives us that gut-level “this feels right” feeling when we see information that matches our beliefs. System 2 could challenge it—but often doesn’t, because it’s lazy and doesn’t like the extra work. False claims spread easily. They match our patterns, slip through the fast system, and often go unchecked by the slow one.

Everyday Examples of Confirmation Bias

Once you know what to look for, confirmation bias shows up everywhere. It’s not confined to abstract psychology experiments—it’s stitched into the fabric of daily life.

Take medicine. A patient who believes in a “miracle cure” may remember only the times it seemed to help, while ignoring the times it did nothing. Anti-vaccine activists cling to anecdotes that confirm their fears and reject mountains of data that don’t. Even doctors can slip, favoring expected diagnoses or overlooking contradictory symptoms—including dismissing women’s pain.

Or consider social media. Platforms are designed to feed us what we “like.” If you like a reel about a particular diet, or a political meme that matches your worldview, the algorithm serves up more of the same. This creates what’s known as a filter bubble—a curated stream of content that reinforces our biases and hides opposing perspectives. In such an environment, it feels like “everyone” agrees with you, because the system is engineered to make it look that way.

And then there’s politics and society. Once we’ve picked a side, we become tribal. We notice stories that make our side look good and dismiss ones that make us look bad. We scrutinize evidence against our opponents while giving a free pass to evidence that flatters us.

In all of these examples, the pattern is the same: confirmation bias smooths the path for beliefs we already hold, while blocking the entry of anything that might disrupt them. It doesn’t just shape what we think—it shapes what we see.

Why It Matters

Confirmation bias isn’t just a quirky mental habit—it has consequences. When patients reject proven treatments for miracle cures, health suffers. When social media feeds us only what we want to see, societies fracture into echo chambers. When politics turns into parallel realities, trust in institutions erodes.

At its core, confirmation bias fuels misinformation and polarization. It keeps us comfortable in our beliefs, but that comfort comes at the cost of truth—and sometimes at the cost of lives.

How to Outsmart Our Own Brains

If confirmation bias is hardwired, does that mean we’re doomed to fall for fake news forever? Not at all. We can’t erase the bias, but we can build habits that work against it.

The scientific method was designed for exactly this problem. Scientists don’t just look for data that supports their hypotheses—they test, replicate, and invite others to try to prove them wrong. Knowledge advances not by defending beliefs, but by challenging them.

The same principle applies in public life. Debate matters because it exposes ideas to criticism. It forces us to consider opposing views, to defend our reasoning, and sometimes, to admit when we’re mistaken.

On an individual level, there are tools we can all use:

- Pause before accepting or sharing information, especially if it feels “too right.”

- Actively seek out disconfirming evidence—ask, what would prove me wrong?

- Diversify your information diet: read sources outside your usual bubble.

- Practice humility: being wrong isn’t a failure; it’s a chance to learn.

These habits take effort. They activate our slower, more deliberate System 2 thinking. And that effort is precisely what helps us resist being misled by the fast, easy shortcuts of bias.

For readers who want to explore the science of misinformation further, Matthew Facciani’s Misguided: Where Misinformation Starts, How It Spreads, and What to Do About It offers a clear, practical guide to understanding fake news and what we can do about it.

Closing

Fake news spreads fast, not because people are foolish, but because our brains are efficient pattern-seekers. Confirmation bias makes falsehoods feel like truth, and in an age of filter bubbles and endless information, that tendency can spiral out of control. The good news is we have tools—science, debate, and deliberate curiosity—that can slow us down and keep us honest.

Next time you see a headline you want to believe, don’t just ask, ‘Is this true?’ Ask, ‘What would convince me it isn’t?’ That single question won’t erase bias, but it can crack open the door to clearer thinking—and in a noisy world, that’s how truth gets a fighting chance.

[…] We notice and remember information that supports our side, and ignore what doesn’t. […]