The science behind our delay tactics — and how to outsmart them

Disclaimer: This post contains affiliate links to Bookshop.org. If you buy through these links, I earn a small commission at no extra cost to you—while supporting indie bookstores and my work.

I’m sitting at my desk, ready to outline this article. That’s the plan, anyway.

Then I hear it — the gentle trickle from my turtle’s tank. Clearly the filter needs changing. I’ll just do that first.

Back at my desk, I notice my nails could use a trim. No — focus. I make a cup of green tea to stay alert.

By the time I sit down again, my cat has sprawled across my notebook. And somehow, I still haven’t written a single sentence.

This isn’t laziness. It’s procrastination — the art of doing everything except the one thing you set out to do.

It happens to all of us, whether we’re students, office workers, or science writers staring down a blank page. It can strike in the middle of the workday, late at night, or any moment we face a task that feels big, boring, or uncomfortable.

Today, we’re going to explore why we procrastinate — using insights from Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow and Gretchen Rubin’s The Four Tendencies. You’ll see how both your brain’s wiring and your personality style shape your delay habits, and you’ll get practical, science-backed strategies for each.

By the end, you’ll know which tendency you are (there’s even a quiz for that) and how to work with your nature instead of fighting it.

The Brain’s Two Systems

I read Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow in the fall of 2024. I learned a lot from it.

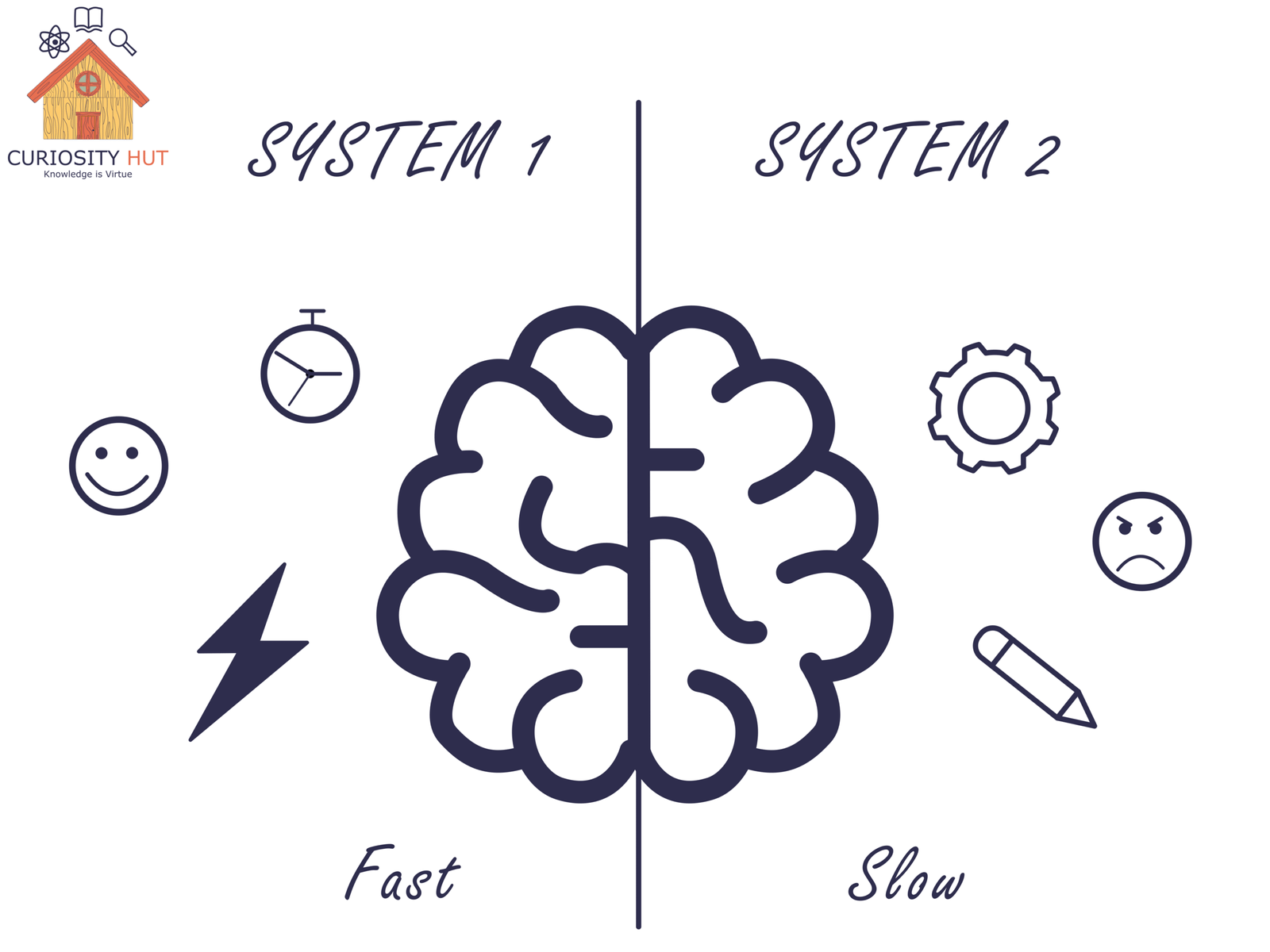

Kahneman describes two ways the brain works. He calls them System 1 and System 2.

System 1 is fast. It works automatically. It uses instincts, gut feelings, and quick impressions. You don’t have to think hard — it just reacts. This is what helps you dodge a ball or finish the sentence “peanut butter and…” without stopping to think.

System 2 is slow. It works with effort. It uses logic, focus, and careful steps. You have to think hard. This is the system you use when solving a math problem or writing a thoughtful email.

System 1 is easy. System 2 is hard. And your brain likes easy.

That’s why we procrastinate. When you face a task that needs System 2 — like filing taxes, studying, or writing — System 1 tries to steer you away. It suggests easier things. Clean the kitchen. Scroll your phone. Refill the turtle tank.

This pull toward easy tasks has a name: present bias. It means our brain gives more value to comfort now than to rewards later. Watching a show feels better in the moment than finishing your report, even if the report will feel great tomorrow.

We can’t switch off present bias. But we can use tricks to outsmart it.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.

How to Outsmart Your Brain’s Two Systems

If System 1 is pulling you toward easy tasks, make the hard task feel easier.

1. Break it down. A big project scares System 1. Cut it into small steps. Don’t “write the whole report.” Just “open the document” or “write one sentence.”

2. Lower the start barrier. Make the first step so small you can’t say no. If you want to read, put the book on your pillow. If you want to run, put on your shoes.

3. Add a small reward now. System 1 likes quick wins. Give yourself something pleasant while you work — music, a warm drink, a nice spot in the sun.

4. Use a short timer. Promise to work for just ten minutes. Often, once you start, you keep going.

5. Remove easy distractions. Put your phone in another room. Close extra browser tabs. Make the “fun” choice harder to reach.

Small changes matter. They give System 2 a chance to step in before System 1 drags you away. And remember to do what works best for you!

Why Avoidance Feels Good

Procrastination isn’t just about laziness or poor willpower. It’s also about feelings — and how our brain protects us from discomfort.

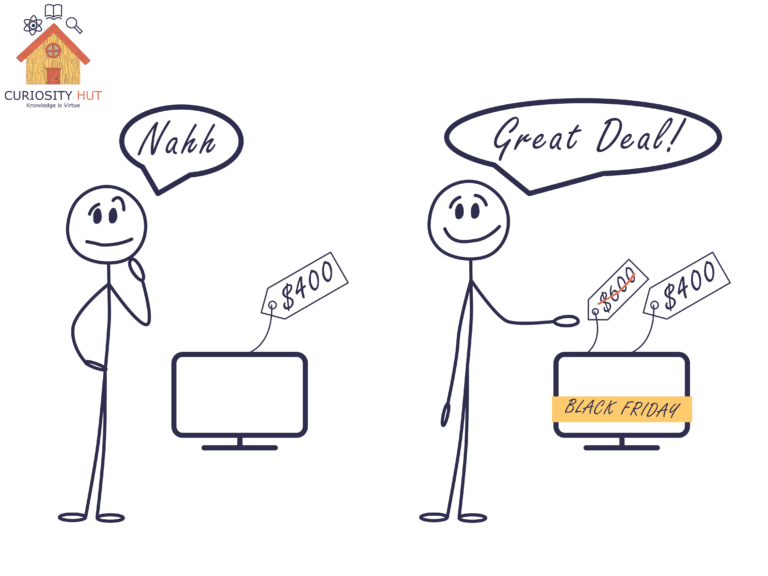

One big reason we avoid tasks is something called loss aversion. It means we feel the pain of losing something more strongly than we feel pleasure from gaining something. For example, missing a deadline feels worse than finishing early feels good.

When a task feels hard, scary, or boring, our brain sees it as a potential “loss” — like losing comfort, peace, or confidence. So it steers us away to protect us from that pain.

When we avoid the task, we get a quick hit of relief. This relief feels good. Our brain learns to repeat this “avoidance → relief” pattern. This is called an avoidance–relief loop. It’s a habit that’s hard to break.

How to Break the Avoidance–Relief Loop

1. Name the feeling. Say to yourself: “I’m anxious about the draft being of low quality.” Naming the feeling makes it less scary.

2. Lower the stakes. Give yourself permission to do a “bad first draft” or a tiny step. It’s okay if it’s messy.

3. Use “temptation bundling.” Pair the hard task with something enjoyable. For example, only listen to your favorite podcast while cleaning or writing. If that doesn’t work, do your favorite task only after you are done with a bad one. I only go to the swimming pool after I am done with house chores.

4. Practice self-compassion. Don’t beat yourself up for procrastinating. It’s natural. Being kind to yourself makes it easier to try again.

The Four Tendencies

Another book that shaped how I think about procrastination is The Four Tendencies by Gretchen Rubin.

It’s about how people respond to expectations — both from themselves and from others.

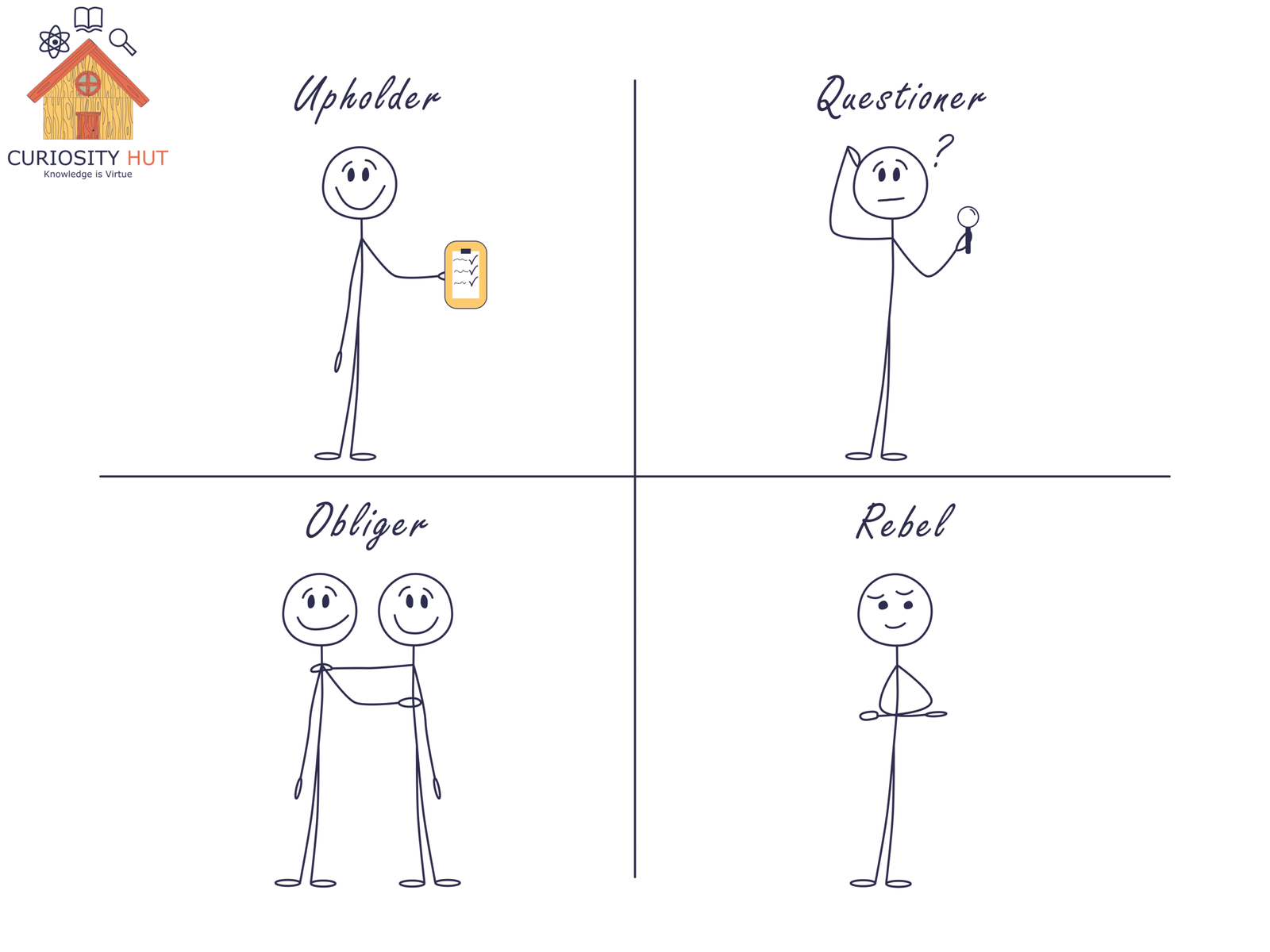

Rubin’s four types are:

1. Upholders

They meet both inner expectations (goals they set for themselves) and outer expectations (requests from others).

They procrastinate when the rules or goals are unclear.

Example: You want to finish a project but the instructions are vague, so you stall.

2. Questioners

They meet expectations only if they make sense to them.

They procrastinate if they doubt the value or logic of the task.

Example: You put off a report because you don’t see why it’s needed.

3. Obligers

They meet outer expectations but struggle with inner ones.

They procrastinate if no one is counting on them.

Example: You miss your own deadline but never a client’s.

4. Rebels

They resist all expectations, inner and outer.

They procrastinate if a task feels forced.

Example: The more someone tells you to do something, the less you want to do it.

If you think this doesn’t apply to you and that you are special, you are a Rebel.

Knowing your type can help you find the right fix. There’s a link at the end of this article to take the official quiz and find out your tendency.

How to Work With Your Tendency

Upholders

Set clear rules and timelines before you start.

Write down exactly what “done” looks like.

If someone else sets the goal, ask them to spell it out in detail.

Questioners

Gather proof that the task matters.

Ask “Why is this important?” until you are satisfied with the answer.

Once you see the value, your motivation will kick in.

Obligers

Add outside accountability.

Tell someone your deadline.

Make it public — post your progress or report to a friend.

The more people counting on you, the more likely you’ll act.

Rebels

Frame the task as your choice.

Find a personal reason to do it that has nothing to do with rules.

Turn it into a challenge or game.

Decide on your own terms, in your own time — but decide.

When you know your tendency, you can stop forcing yourself to work like someone you’re not. You can match your strategy to your nature.

Recap: Procrastination Unpacked

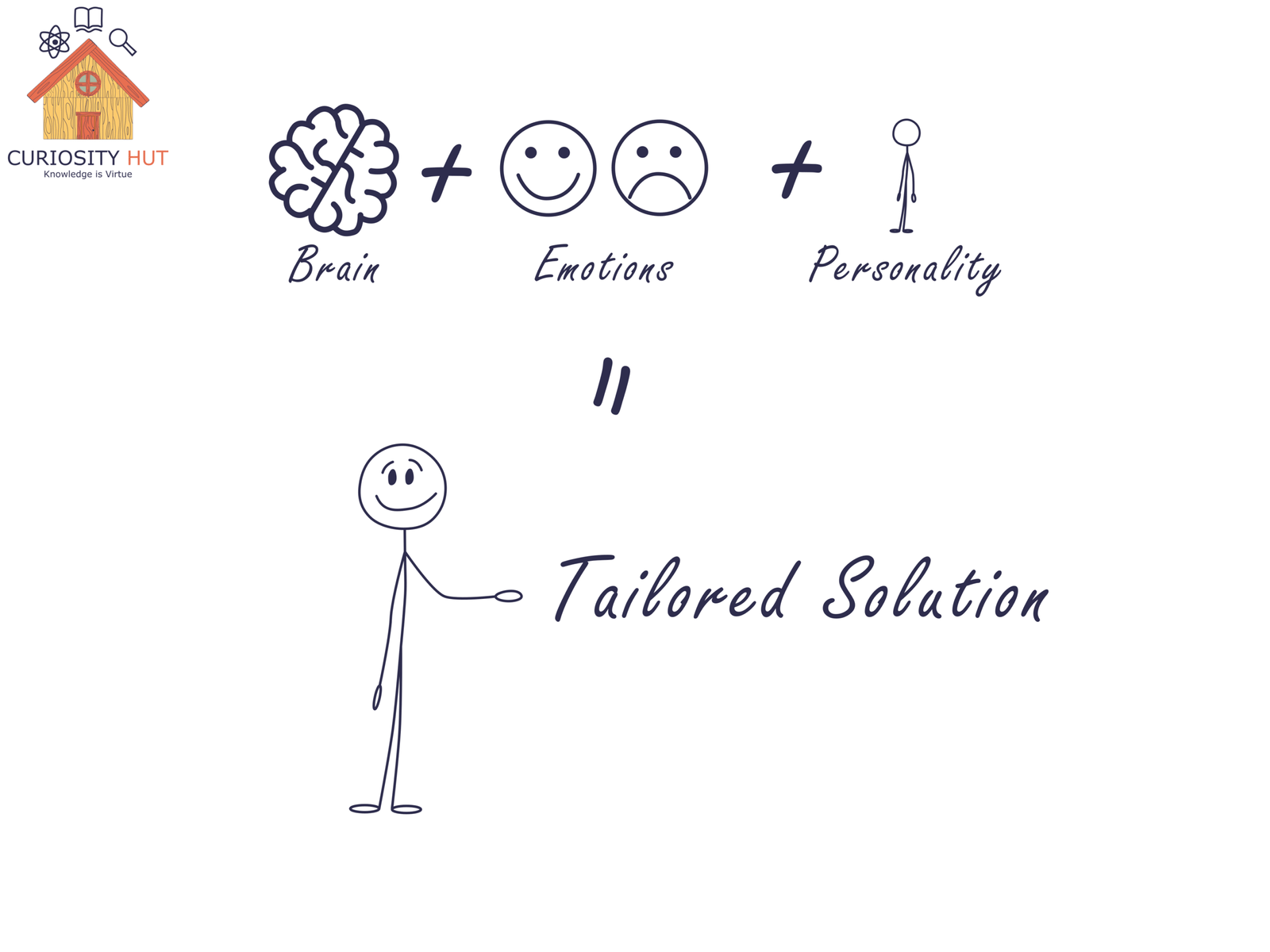

Procrastination isn’t laziness. It’s your brain and personality working in familiar patterns:

- Your brain’s System 1 pushes you toward comfort, away from effort.

- Present bias tricks you into choosing now over later.

- Your emotions reinforce this, rewarding avoidance with relief.

- Your personality tendency shapes how that avoidance looks.

Understanding both your brain wiring and your personality helps you choose strategies that actually work for you. The generic advice — “just do it,” “work harder,” or “stop being lazy” — has never helped anyone..

And Now… A Gentle Ending

You’re not broken. You’re human.

Your brain evolved to conserve energy and seek comfort. That’s not a flaw—it’s instinct.

By learning how your mind and your type work, you can guide your habits rather than chase them.

So maybe—just maybe—you’ll get back to outlining this article… right after you feed the turtle (or persuade your cat to move off your notebook).

And hey, if you’re curious about your tendency, here’s your next step:

Take the official Four Tendencies quiz here.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.