From bloodstream chaos to molecular precision—and how drugs find their effects without a map.

Watch the news for more than five minutes, and you get a headache.

Your jaw tightens. Your shoulders creep upward. A dull pressure blooms behind your eyes. You reach for a painkiller, swallow it, and almost without thinking, expect it to go straight to the problem. To your head. To that exact, pulsing spot where the day has become too loud.

This expectation feels reasonable. After all, the pill works. Relief arrives. The headache loosens its grip. Case closed.

Except none of that required the medicine to know where your head is.

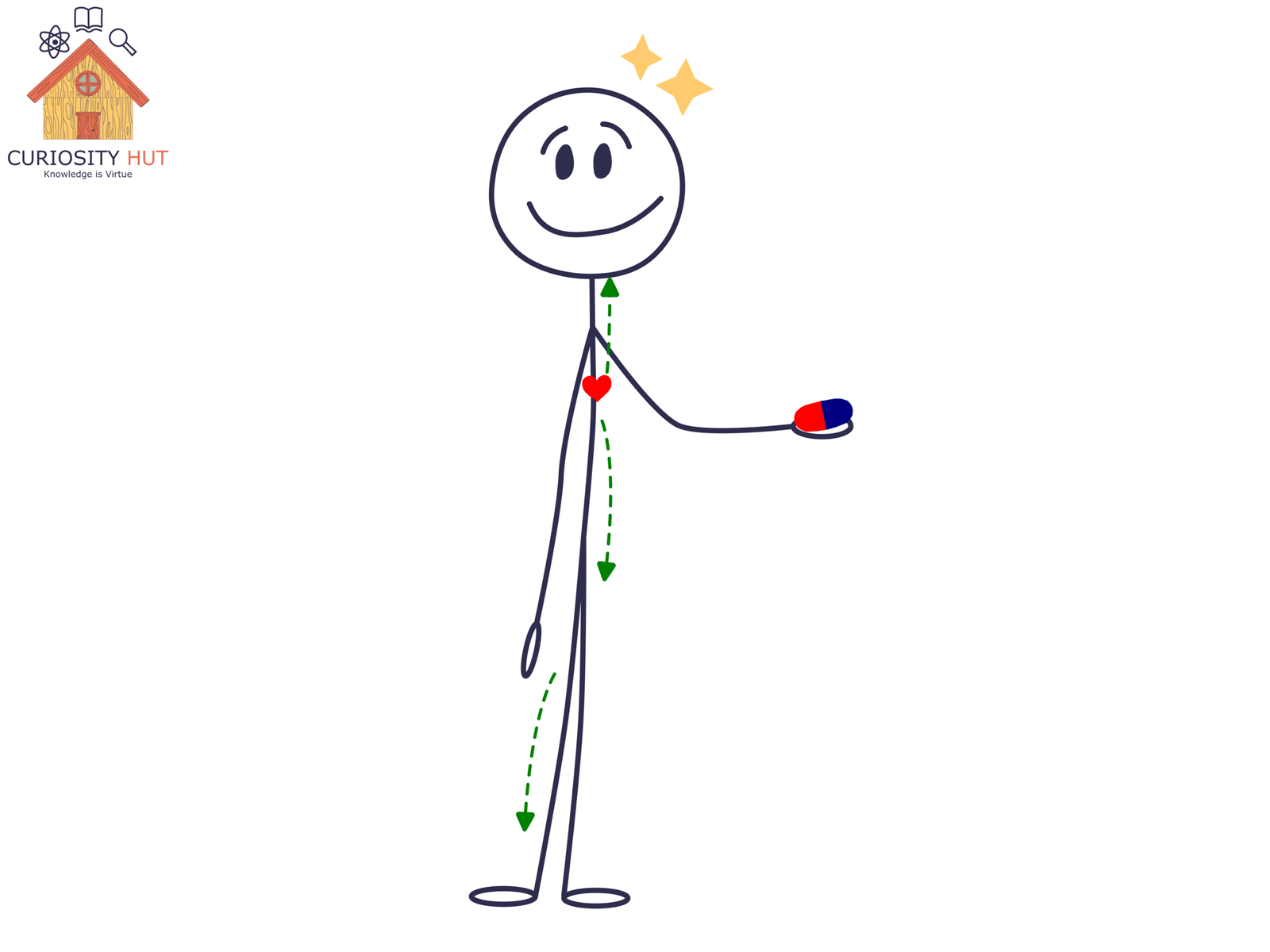

The pill didn’t receive instructions. It wasn’t dispatched to a coordinate marked left temple. Once swallowed, it entered one of the messiest environments imaginable: your bloodstream. A fast-moving, branching river that touches nearly every cell in your body.

Which raises a strange question we rarely ask. If medicine doesn’t know where to go, how does it so often end up doing the right thing?

The bloodstream is not a delivery service

Once a drug enters your bloodstream, it loses all sense of place. Not metaphorically—literally. Molecules don’t carry addresses or follow routes. They drift, collide, and circulate.

Within minutes, that painkiller has passed through your brain, your liver, your kidneys, your toes. It has washed over tissues that have nothing to do with your headache. This isn’t a failure of design. It’s how circulation works.

If this surprises you, side effects shouldn’t. Drowsiness, dry mouth, nausea—these are clues. They tell us the drug didn’t stay politely confined to the problem area. It went everywhere.

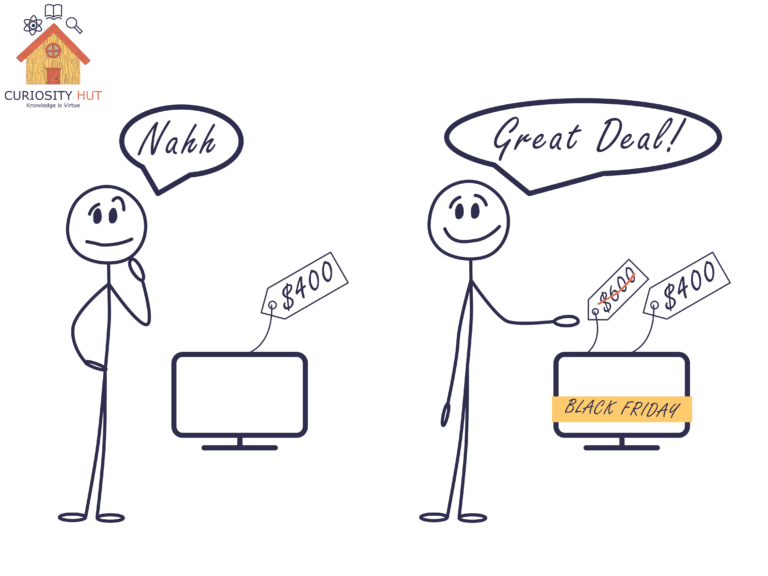

And yet something selective happens. Your headache fades, but your vision doesn’t blur. Your feet don’t go numb. The medicine spreads broadly, but its effects do not.

This is the first key tension in how drugs work: distribution is wide, action is narrow. The explanation isn’t navigation. It’s biology.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.

Receptors decide what matters

Every cell in your body is surrounded by molecular noise. Hormones, nutrients, waste products, stray chemicals—all floating past, all the time. If cells responded to everything they encountered, nothing would function for long.

Instead, cells listen selectively.

They do this using receptors: proteins embedded in the cell surface, shaped to respond only to specific molecules. When the right molecule binds to the right receptor, a signal is triggered. When it doesn’t, nothing happens. The molecule can pass by a thousand times without consequence.

This is how a drug can be everywhere and still matter only somewhere.

Pain-relieving drugs work because certain cells—especially those involved in pain signaling—carry receptors that respond to them. Other cells lack these receptors or express them in very small numbers. The drug passes through unnoticed.

Receptor density matters too. A tissue packed with responsive receptors will react strongly. Another with only a few will barely register the drug’s presence.

There’s no intent here. No recognition. Just shape, probability, and repeated collisions. Specificity emerges not because the drug aims, but because only some cells are built to care.

How does medicine know where to go?

From bloodstream chaos to molecular precision—and how drugs find their effects without…

Dopamine: Why Your Phone Feels Like a Hit of Life

How a tiny molecule shapes motivation, pleasure, addiction, and modern life. A…

Chemistry shapes where drugs can go

Even before receptors come into play, chemistry quietly limits a drug’s journey.

Some molecules dissolve easily in water. Others prefer fat. This simple difference shapes how they move through the body, how long they linger, and which tissues they can enter.

The brain is the most famous example. It is protected by the blood–brain barrier, a tightly regulated filter that blocks many substances from leaving the bloodstream and entering neural tissue. This is why some drugs never affect your thoughts or mood at all—they simply can’t get in.

To reach the brain, a molecule must have the right chemical traits. Not too large. Not too reactive. Just slippery enough to cross without setting off alarms.

Other tissues create their own biases. Fat stores certain drugs and releases them slowly. Bone can trap others for years. The liver aggressively modifies many compounds the moment they arrive.

None of this is targeted in the everyday sense. But it isn’t random either. The body isn’t an empty container—it’s a landscape. Chemistry determines which paths are open, which are blocked, and which lead to dead ends.

By the time a drug has finished spreading, being filtered, and bumping into receptors, its “destination” has already been decided—without a single act of direction.

Depression drugs and the hardest destination of all—the brain

If painkillers reveal how medicine works without direction, antidepressants reveal how strange that idea becomes once the target isn’t a place at all.

Depression doesn’t live in a single spot in the brain. There is no “sadness center” waiting for chemical repair. Instead, there are networks—circuits of neurons talking to each other using chemical signals called neurotransmitters. Serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine. Names that get simplified in headlines, but in reality describe sprawling, overlapping systems.

Antidepressants don’t navigate to a mood. They face a more basic challenge first: getting into the brain at all. Only molecules with the right chemical properties can cross the blood–brain barrier. Many never make it past this gatekeeper.

Those that do don’t arrive at a precise destination. They spread widely, bathing large regions of the brain. Their selectivity comes not from location, but from which signaling systems they influence. A drug that slows the reuptake of serotonin changes how long that signal lingers between neurons.

Over time—often weeks—the brain adapts. Circuits rebalance. Patterns of activity shift.

The delay matters. If antidepressants worked by “going to the right spot,” their effects would be immediate. Instead, they work by nudging a system and letting biology respond.

Here, more clearly than anywhere else, medicine doesn’t fix a problem. It changes the conditions under which the problem is made.

When medicine really tries to aim

So far, everything sounds imprecise. Drugs drift. Cells decide whether to care. Chemistry opens some doors and closes others. If that’s the whole story, it’s fair to wonder whether medicine ever truly targets anything.

In some cases, it does—very hard.

Modern cancer therapies offer the clearest example. Certain cancer cells display unusual proteins on their surfaces, molecular flags that distinguish them from healthy neighbors. Researchers have learned to build antibodies that bind to those markers, then attach drugs to the antibodies themselves.

The result is a kind of guided delivery. Not a missile, exactly—but a package more likely to be opened by the right cell.

Other strategies rely on packaging rather than recognition. Drugs can be enclosed in nanoparticles designed to release their contents only under specific conditions, such as the acidic environment inside a tumor. Others are engineered to become active only after being modified by enzymes found primarily in diseased tissue.

Even here, perfection is a fantasy. Targeted drugs still circulate widely. They still miss some intended cells and affect some unintended ones. What changes is the math. The odds tilt.

Biology is shared, crowded, and reused. Absolute precision is rare. Progress comes from stacking probabilities in the right direction—and accepting that control is always partial.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.

The liver—the body’s chemical editor

Even after a drug has spread through the body, crossed barriers, and bound to receptors, its journey isn’t over. In many ways, it’s just being tolerated.

The liver sits downstream of the bloodstream like an editor with a red pen. Its job is not to help drugs work, but to change them. Enzymes slice, tweak, and tag foreign molecules so they can be removed. Some drugs are inactivated quickly. Others are transformed into new compounds—sometimes weaker, sometimes stronger.

This process explains why dose matters. Swallow too little, and the liver dismantles the drug before it has much effect. Swallow too much, and the system is overwhelmed. Timing matters too. Sustained-release pills, patches, and injections are all attempts to manage this chemical gauntlet.

Crucially, the liver doesn’t know what the drug is for. It treats a painkiller, an antidepressant, and a toxin with the same suspicion. From the body’s perspective, medicine is a guest on probation.

Why side effects are built in, not mistakes

By now, the pattern should be clear. Drugs go everywhere. Receptors are reused across tissues. Chemistry opens some doors and closes others. The liver edits relentlessly.

Side effects aren’t glitches in this system. They’re signatures of it.

The same receptor that reduces pain in one part of the body may slow digestion in another. The same neurotransmitter involved in mood also regulates sleep, appetite, and attention. Evolution didn’t design these systems with pharmacology in mind. It reused what worked.

This is why isolating a single effect is so hard. It’s not that medicine lacks sophistication. It’s that living systems are deeply interconnected.

The real aim of treatment, then, isn’t surgical precision. It’s useful imbalance—shifting the system enough to relieve suffering without tipping something else too far.

Medicine doesn’t know—biology responds

Return to the headache.

That pill you swallowed didn’t hunt down pain. It flooded your body, crossed barriers, bumped into receptors, got edited by your liver, and quietly altered the odds inside your nervous system. Relief emerged not because the drug was smart, but because your body responded.

This is the deeper truth behind modern medicine. Drugs don’t know where to go. They don’t recognize diseases. They don’t fix broken parts.

They interact.

And from those interactions—messy, probabilistic, and constrained by biology—something remarkably human happens: suffering eases.

Precision is improving. Targeting is getting better. But the intelligence has always been there—not in the medicine, but in the living system it enters.

Drugs don’t find their targets. Targets reveal themselves.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.