From the Moon landing’s hand-woven wires to the silicon chips in your pocket.

In 1969, Apollo 11 carried three astronauts to the Moon and back with a guidance computer. It had 72 kilobytes of memory. That’s less than the size of a single photo you might send on your phone today. Back then, memory was bulky, fragile, and costly. NASA had people weaving wires by hand to stitch the programs together. Fast-forward fifty years. Α fingernail-sized memory card holds thousands of pieces of information. We went from woven copper threads to dense silicon chips in a few decades.

From Apollo to Your Pocket

The Apollo Guidance Computer used something called core rope memory. It looked more like a textile project than electronics. It was many tiny wires woven through or around magnetic cores. Each crossing encoded a one or a zero. The code wasn’t typed in. People stitched it in, permanent and unchangeable. These people were textile workers with specialized skills. They were often described as “little old ladies” in news reports of the time. The ladies treated the code like embroidery.

This setup gave Apollo astronauts stable, non-volatile memory. The instructions stayed in place even when the computer was off. But it also meant updates were slow and costly. To change the program, engineers had to weave a brand-new block of memory.

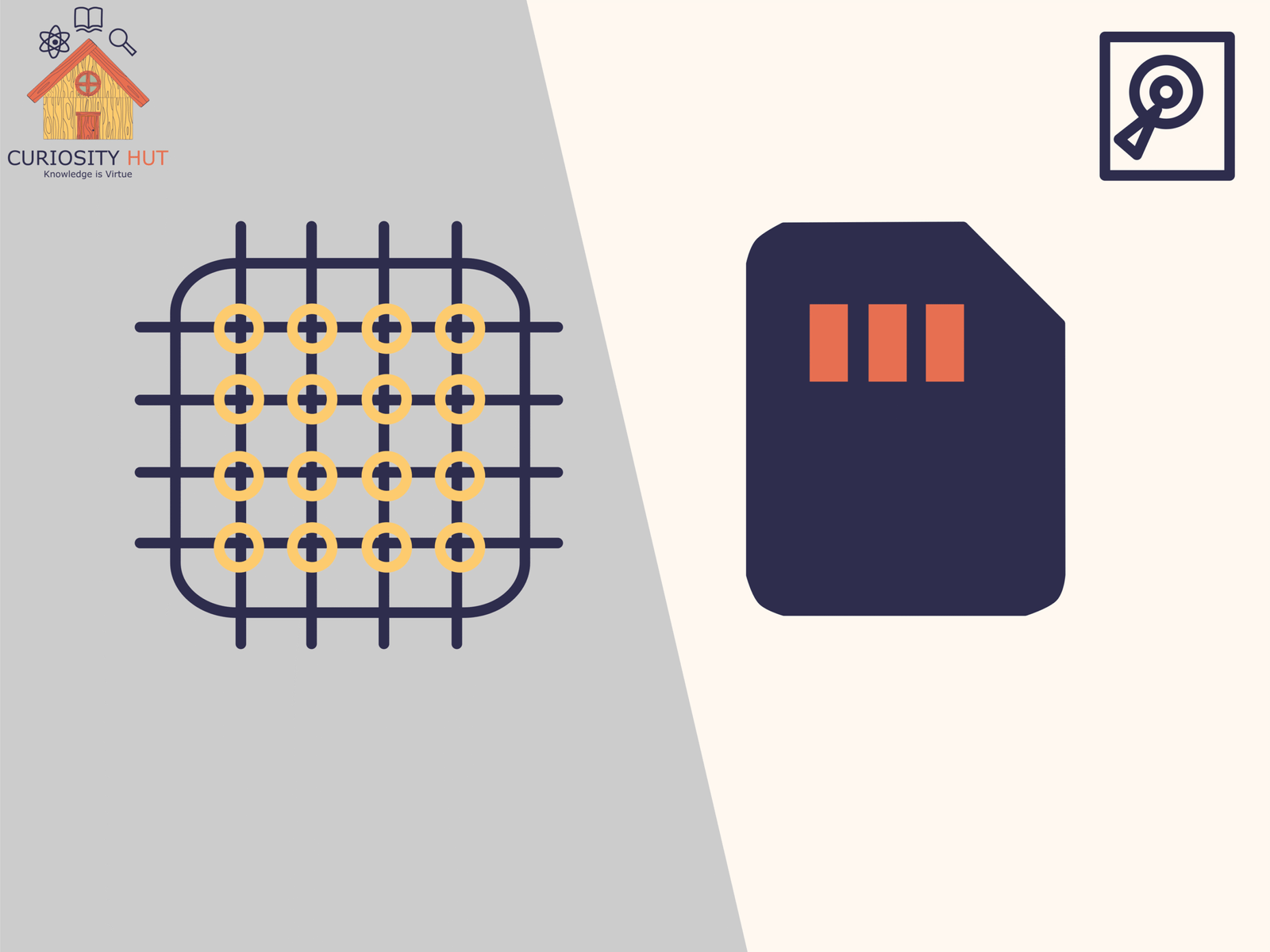

Now compare that to the tiny flash chip in a USB stick. The same volume of material that once stored only a few kilobytes now holds gigabytes. That is millions of times more. Instead of woven wires, we trap electrons in microscopic transistors etched into silicon.

Volatile vs. Non-Volatile Memory

Not all memory behaves the same way.

Volatile memory disappears the moment you cut the power. It is like a whiteboard. It’s fast and easy to write on, but the moment you switch off the lights, the board is clean. That’s what your computer’s RAM does. RAM is great for working with data in the moment, but nothing is saved once the power drops.

Non-volatile memory is like ink on paper. Once written, it stays put until you erase it. That’s how storage works, whether it’s a hard drive, an SSD, or the core rope memory that steered Apollo 11.

The two types work together. Volatile memory keeps things moving fast, while non-volatile memory keeps the record safe. You need both, or your computer would either forget everything at shutdown or run very slowly.

How Storage Really Works

There are two main ways today’s computers store data: by moving magnets or by trapping electrons.

Hard drives (HDDs) use magnets. Picture a record player. Instead of grooves in vinyl, the disk is coated with magnetic material. A tiny head floats above the spinning surface, flipping regions of the disk north or south to record a one or a zero. It’s mechanical, precise, and surprisingly durable. The downside? Moving parts take time. Finding data is like skipping to a track on a record—you wait for the needle to land in the right spot.

Solid-state drives (SSDs) use electricity. Imagine a sheet of invisible lockboxes, each one holding or releasing a few electrons. Those trapped electrons are the bits of your data. No moving parts, no spinning disk. That makes SSDs much faster. Imagine jumping instantly to the right song on a playlist instead of waiting for the record to spin.

Each has tradeoffs. HDDs are cheaper for large storage and can survive being rewritten many times. SSDs are faster and smaller, but wear out slowly as electrons leak from their tiny traps. It’s the difference between storing your notes in a sturdy filing cabinet versus in a lightning-fast but delicate flash of memory.

Deleted Doesn’t Mean Gone

When you hit delete, your computer doesn’t actually wipe the data. It removes the pointer telling the system where to find it. Like pulling the label off a filing cabinet drawer while the papers are still inside.

On a hard drive, those magnetic patterns stay in place until new data overwrites them. With the right tools, pieces of “deleted” files can often be recovered. That’s why digital forensics can pull surprising details from old disks.

SSDs make this trickier. They scatter data across many cells to extend their lifespan. We call that process wear leveling. When you delete a file, the electrons don’t vanish immediately. Fragments may linger, but recovery is harder. Modern SSDs also use “garbage collection” to clean up space, which can erase traces faster.

This is why secure deletion matters. Emptying the trash doesn’t guarantee your data is gone. Erasing it requires overwriting or specialized tools. Especially if you don’t want anyone peeking into the digital past.

The Future of Memory

Memory keeps shrinking and multiplying. Engineers now stack memory cells in 3D, cramming more data into the same tiny chip. Other labs are testing exotic ideas. For example, phase-change materials that switch states with heat. Or memristors that mimic brain-like patterns. The goal is always the same: faster, denser, and more reliable ways to store the flood of digital life.

Half a century ago, astronauts went to the Moon with memory woven by hand, measured in kilobytes. Today, billions of invisible transistors etched on silicon can hold entire worlds of information on something smaller than a coin.

Closing Thought

The leap from Apollo’s rope memory to your pocket-sized SSD shows how far we’ve come. What once filled a room now holds your photos, messages, and favorite songs. Memory isn’t about numbers or speed—it’s about trust. We depend on it to keep our digital lives safe, ready to recall at a moment’s notice.