How the city lifted itself—literally—to survive disease, mud, and modern life

I walked out of the National Museum of Mexican Art and headed east along 19th Street in Pilsen. Something felt off. Many apartment buildings looked…sunken. Their windows sat at a normal height, yet the living spaces behind them were nearly a story below the sidewalk. Front doors—once at ground level—were now reached by wooden stairs leading up or down to what had originally been a building’s second floor.

It reminded me of Thessaloniki, Greece. There, Byzantine churches and the Roman Agora sit below street level, buried under centuries of construction. Thessaloniki is nearly 2,000 years old, layered like an archaeological cake. Buildings sink because time piles on top of them.

But Chicago was founded in 1837. It hasn’t had time to sink.

So what happened?

The answer is stranger—and more impressive—than slow burial. Chicago didn’t sink. It rose.

In its early years, Chicago sat almost level with Lake Michigan and the Chicago River. When it rained, water had nowhere to go. Streets turned to mud. Waste pooled. Disease spread. Cholera and typhoid killed residents, and businesses struggled to function in a city that couldn’t drain itself.

The city had a choice: accept the swamp, or out-engineer it.

City leaders hired engineers and gave them an unusual mandate—fix the problem, however radical the solution. What followed is what happens when politics steps aside, and engineering takes the wheel.

The solution was a revolutionary sewer system. But for sewage to flow, gravity had to help. That meant raising Chicago’s street level by four to ten feet.

There was a catch. Once the streets were raised, buildings would sit below them.

So the city left it up to property owners: move your building, lift it, or live below the sidewalk. Many homeowners—especially in working-class neighborhoods—chose the cheapest option. They added stairs or small bridges from their second floor to the newly elevated street, leaving the original ground floor partially buried.

You can still see this today in neighborhoods like Pilsen, Bridgeport, and Back of the Yards.

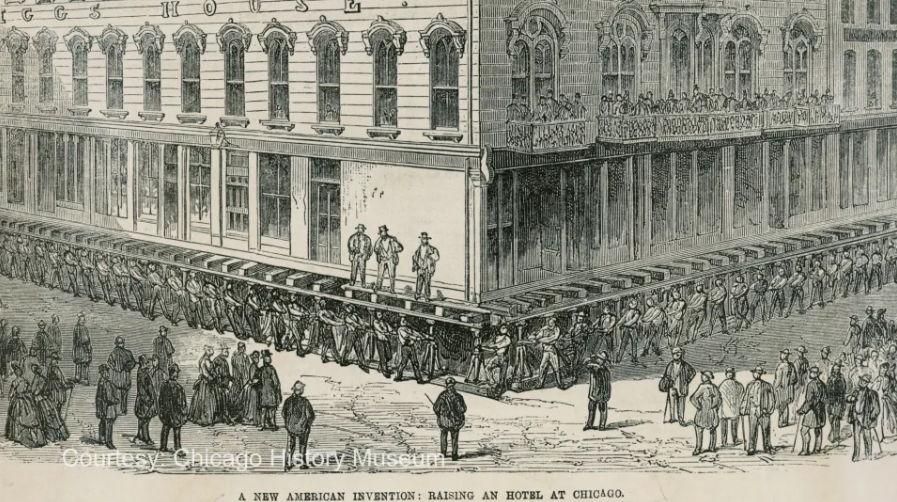

Downtown, of course, was another story. Chicago couldn’t afford to sink its commercial core. So engineers did something extraordinary.

Beginning in 1858, entire downtown buildings were lifted into the air using thousands of jack screws. One by one, then by the dozens. In 1860, a full block of buildings on Lake Street between Clark and LaSalle rose six feet, powered by the synchronized turning of 6,000 screws.

The following year, the Tremont House—a six-story luxury hotel at Lake and Dearborn—was lifted six feet while fully occupied. George Pullman, then in the building-raising business, won the contract by promising not to disturb a single guest or break a single window. He delivered. One guest reportedly checked out to find that windows once at eye level were now above his head.

By the early 1870s, as many as fifty major downtown buildings had been raised.

Much of that progress was erased by the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. But the sewer system remained. The city had changed its relationship with water—and with disease—forever.

Before closing, there’s a deeper irony worth noticing.

By the 1850s, Chicago—an exploding industrial city—still relied on open ditches, backyard privies, and muddy streets where human and animal waste drained wherever gravity allowed. In that sense, it lagged behind several European cities. Paris had expanded its sewer network in the early 1800s. London began building massive underground interceptors after the Great Stink of 1858. Berlin and Vienna were laying planned drainage systems by mid-century.

And the gap stretches much further back. Nearly 4,000 years earlier, cities of the Indus Valley like Mohenjo-Daro had covered street drains and household connections. Minoan Crete used terracotta pipes and flushing systems. Teotihuacan engineered channels to manage water across a dense urban grid.

The problem was never intelligence. It was memory.

Urban sanitation is something civilizations learn, forget, and relearn—usually after disease makes neglect impossible. Chicago learned its lesson the hard way. Then it did something rare.

It lifted itself out of the mud.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.