A pair of boots in Istanbul taught me why the first offer sticks—and how it quietly shapes every judgment that follows.

Disclaimer: This post contains affiliate links to Bookshop.org. If you buy through these links, I earn a small commission at no extra cost to you, while supporting indie bookstores and my work.

The Grand Bazaar in Istanbul is a place where numbers fly faster than swallows. My father and I were drifting through the maze of leather stalls when a merchant spotted us, heard us speaking in Greek, and—without missing a beat—quoted €80 for a pair of boots. My father smiled, confident he knew the game, and fired back with €30. The merchant dropped to €70. My father patted his wallet, announced he only carried €50, and the deal was sealed with a handshake.

Hours later, I discovered the boots sold for about €20. The merchant’s first offer wasn’t just a price—it was gravity. Everything we did afterward revolved around it.

What Is Anchoring?

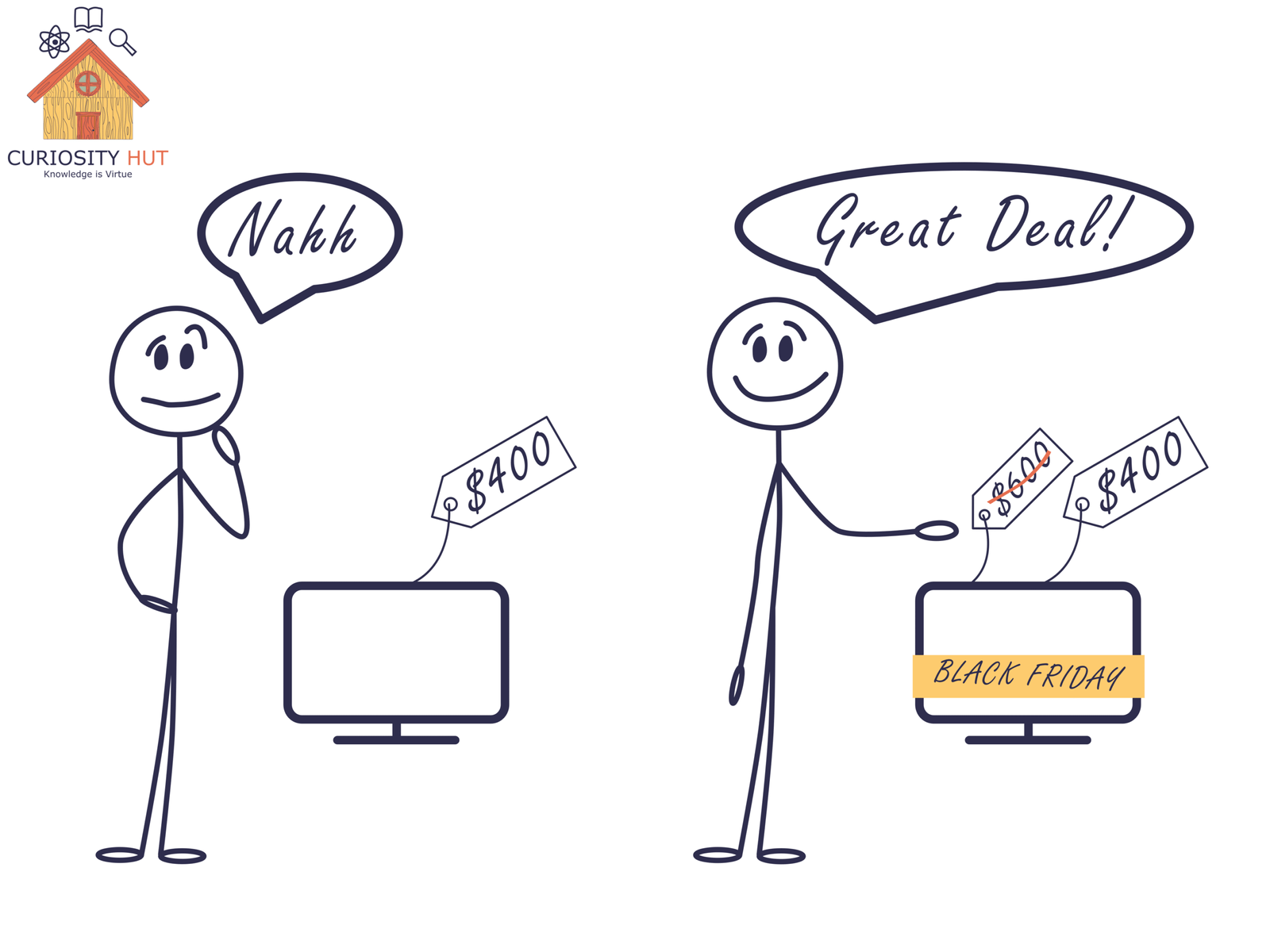

Anchoring is the mind’s habit of grabbing the first number it sees and using it as a reference point, even when that number has no authority. Once that starting value is in place, every judgment bends toward it. It’s a mental shortcut that works beautifully in math class and disastrously in open-air markets.

Anchoring operates in two ways, like a tag team.

Anchoring as Adjustment

This one feels intuitive: you hear a number and adjust away from it—but the adjustment is always too small. Imagine someone asking whether the average winter temperature in Helsinki is higher or lower than 20°C (68°F). Even if you know it’s lower, your estimate drifts only a little below the anchor. The initial number acts like mental glue; part of it sticks no matter what.

A classic everyday example is the “suggested donation” at a museum. The sign says $30. You balk, drop in $15—and still pay far more than you would have if no number had been planted.

Anchoring as Priming Effect

Anchors also prime your thinking. The first number doesn’t just sit there; it activates related ideas in memory. Large numbers make your mental frame expand; small numbers shrink it. You don’t notice it, but your judgment quietly shifts.

Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow demonstrates this with a roulette-wheel experiment. Participants spun a wheel rigged to land on either 10 or 65. Then they guessed what percentage of African countries belonged to the UN. Those who saw 10 guessed far lower than those who saw 65—even though the wheel was irrelevant. The number had nudged their mind.

Sticky starting points and subtle priming combine to make the first offer feel heavier than it should, turning a random number into a compass your mind follows automatically.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.

Anchoring Leaves a Measurable Footprint

Most psychological quirks resist measurement, but anchoring doesn’t. Researchers use an anchoring index—the percentage of movement in people’s guesses caused by the anchor itself. In the roulette-wheel study, the meaningless number nudged estimates up or down predictably. Anchoring is unusually measurable, which is why behavioral scientists study it so closely.

Anchors Everywhere

Anchoring slips into everyday life, often unnoticed.

Experts and novices alike are steered by anchors. The experts are just more certain they aren’t.

Why Splitting the Difference Works Against You

Negotiation guru Chris Voss notes: meeting in the middle usually just surrenders ground with better lighting. A high first offer defines the landscape. Splitting drags you toward their anchor, not toward fairness.

Loss aversion deepens the trap. Your instinct is to avoid the pain of overpaying rather than to seek gain. That’s why my father felt victorious paying €50 instead of €80—the anchor turned €50 into relief rather than overpayment.

The solution: make the initial anchor untenable. Push back hard. Signal it’s outside the realm of possibility. Threaten to walk away if necessary. The goal isn’t drama; it’s resetting the conversation.

Once the anchor is broken, offer a well-shaped range. Plant a new reference point that keeps you out of the gravity field of the opening absurdity. This is the difference between reacting to someone else’s frame and shaping the frame yourself—a shift that echoes beyond bazaars and boots.

Using Anchoring to Your Advantage

Anchoring works both ways. When you make the first move, the number becomes your opening frame.

Keep your anchor calm and grounded. Controlled anchors feel like information; wild ones feel like noise. Done well, the first number quietly steers the discussion.

How to Shield Yourself from Anchors

- Buy time: Pause before reacting and build your own estimate. A self-generated reference point blunts external anchors.

- Check multiple sources: Compare prices, salaries, or figures. A plausible range reduces fixation on any single number.

- Reject absurd offers outright: Not politely “too high”—declare them unrealistic. Breaking the spell frees your judgment.

Therefore…

Anchoring isn’t just an abstract quirk—it shapes real decisions every day. From haggling in the Grand Bazaar to negotiating raises or grants, the first number on the table shapes everything that follows. Awareness allows you to resist unwanted influence—or wield the bias to your advantage.

The first number matters. Know its pull, and you can resist it—or make it work for you.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.