I’m a Panathinaikos fan by birth and a Cubs fan by relocation. Two teams, two sports, zero logic. The Cubs haven’t won a World Series since 2016, and the Panathinaikos football team has spent the past decade perfecting the art of disappointment. But our basketball team? That’s a different story as we make clubs like Barcelona and Real Madrid look like little puppies.

So why am I loyal to both a dynasty and a disaster? Why do I still chant the same colors even when the scoreboard says I shouldn’t? Because facts clearly don’t decide who we support, whether it’s a team, a religion, a political party, or even a phone brand. (Android is obviously superior. I will not be taking questions.)

If belief isn’t about evidence, then what is it about?

We Don’t Choose Our Teams—We Inherit Them

Humans didn’t evolve to be lone thinkers—we evolved to be tribal. Belonging to a group once meant survival: protection, shared resources, a sense of “us” against everything outside the firelight. Today the predators are gone, but the instinct is still running the show. We look for teams to join, not because they’re rationally better, but because they give us identity, safety, and meaning.

A “team” can be anything: a football club, a nation, a religion, a political party, a brand, a fandom (Marvel vs. DC), a university, even a celebrity feud. The content doesn’t matter. The belonging does.

We like to think we choose our beliefs based on evidence, but most of the time we’re just adopting the beliefs that come with the group we’ve already chosen. Identity comes first; reasoning shows up later to justify it.

That’s why supporting a losing team still feels right, and why changing a deeply held belief can feel like betrayal rather than growth. We’re not just defending ideas—we’re defending who we are.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.

The Brain Plays Favorites: Biases That Protect the Team

Belonging feels good, but it comes with a hidden cost: once we identify with a group, our brain stops acting like a neutral judge and starts acting like a defense lawyer. We don’t just believe in our team—we protect it, even when the facts are against us.

Here’s how that protection system works.

Confirmation Bias

We notice and remember information that supports our side, and ignore what doesn’t.

Example: A Lord of the Rings fan sees every glowing review as “proof it’s still the greatest franchise,” but dismisses the fact that I fall asleep every time I try to watch it.

Motivated Reasoning

We don’t analyze information to find the truth—we analyze it to defend what we already believe.

Example: A diehard political supporter excuses scandals from their own candidate (“taken out of context”) but sees the same behavior in the opposing candidate as unforgivable.

Us vs. Them Bias

We treat members of our group as complex individuals and outsiders as stereotypes.

Example: A university student says “people at our school are all different and interesting,” but talks about the rival school like everyone there is the same kind of idiot.

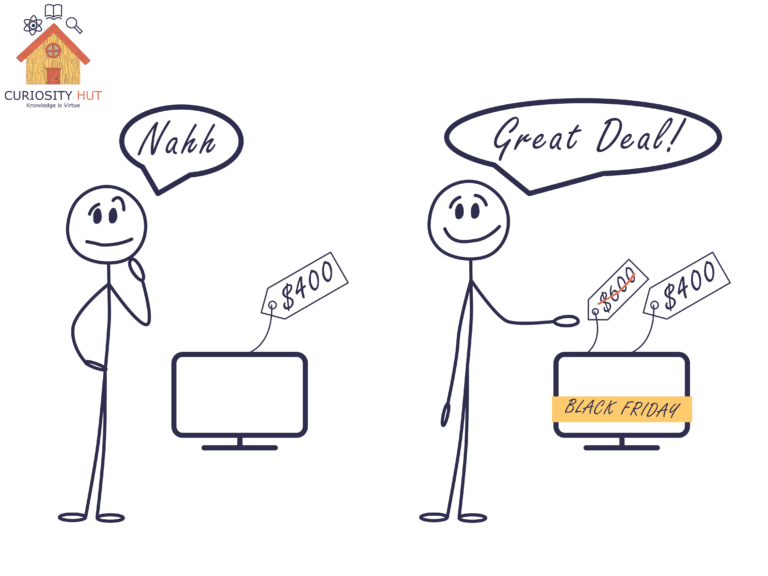

Cognitive Dissonance

When reality conflicts with our beliefs, we don’t usually change the belief—we rewrite the reality.

Example: A crypto bro whose coin crashes 80% insists it’s just a “temporary dip” and part of the long-term plan—plus some nonsense about blockchain.

The Identity Trap (Facciani’s Point)

Psychologist Matthew Facciani argues in Misguided that the biggest barrier to truth isn’t lack of information—it’s the way beliefs fuse with identity. When an idea becomes part of who we are, disagreeing with it feels like a personal attack. That’s why arguing with facts often backfires. You’re not just challenging someone’s beliefs—you’re threatening their sense of self.

And here’s the key insight:

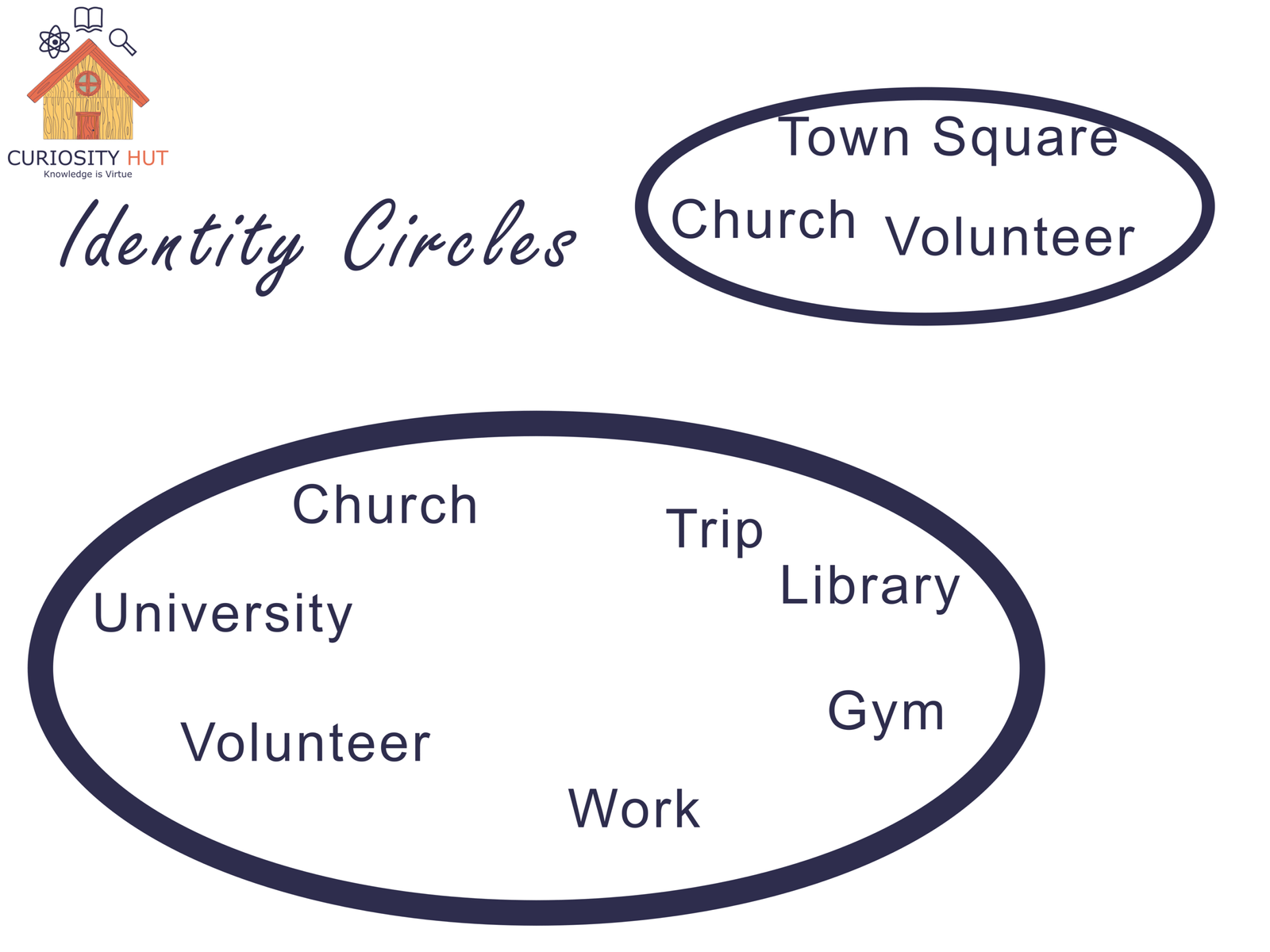

The smaller your identity circle, the more fragile it is.

The wider your identity circle, the more open you become.

If someone defines themselves by one narrow label—one party, one religion, one nation, one team—their worldview is easier to threaten, so they defend it harder. But people who expand their identity (travel, university, diverse friends, new experiences) have more ways of seeing themselves and are less threatened by new ideas.

That’s why people who leave their hometown, study abroad, or spend time with different cultures often become more flexible in their thinking. They’re not “indoctrinated”—they’ve just widened the circle of who counts as “us.”

Facciani’s book is basically a manual for understanding why political polarization feels so personal. It’s not a war of ideas—it’s a war of identities.

How to Think Better Without Losing Your Team

You don’t have to abandon your sense of belonging to escape the endless cycle of “I’m right, you’re wrong.” The goal isn’t to stop caring about your team—it’s to stop letting your team do the thinking for you. There are a few habits that make that possible.

Pause Before You Defend

Most people aren’t attacking you—they’re expressing their own identity. That alone can defuse half of all arguments. If your first instinct is to fire back, try asking: What part of me feels threatened right now? That tiny gap between reaction and response is where thinking happens.

Disagree Without Dehumanizing

You can challenge someone’s ideas without challenging their worth. Curiosity beats confrontation almost every time. You’re not agreeing—you’re just trying to understand how they got there. That said, some beliefs (fascism, racism, dehumanizing ideologies) don’t need gentle curiosity. Some ideas deserve a kick in the teeth.

Look for Evidence That Proves You Wrong

Actively searching for disconfirming evidence is one of the most reliable ways to escape misinformation—and it’s the exact opposite of what our brain wants to do. If you’re never surprised by what you learn, you’re not learning.

Separate Who You Are from What You Believe

A belief is a tool, not a body part. Philosopher Eckhart Tolle puts this simply: you are not your thoughts. In The Power of Now, he suggests noticing your thoughts the way you’d notice clouds passing by—observing them instead of becoming them. That mental distance is what allows beliefs to evolve instead of calcify.

The point isn’t to stop having teams. The point is to stop mistaking your team for the truth. The wider your identity, the more room you have to change your mind without feeling like you’re losing yourself.

Takeaway

I’m still convinced Panathinaikos is the best team on Earth, Chicago is the best city in the U.S., Paxoi is the most beautiful island in the world, and my yiayia’s moussaka is the single greatest dish in the known universe. None of that is objective. All of it feels true because it’s part of who I am. And that’s the whole point.

When you hit people with facts the way you’d hit a piñata, you’re not correcting them—you’re threatening their identity. That’s why debates turn into battles (or full-on shitshows) and why nobody walks away persuaded. If belief is tied to belonging, then persuasion starts not with a counterargument, but with a gentle question.

Curiosity opens doors. Certainty slams them.

Subscribe to my Free Newsletter

Sign up for blog updates, science stories, riddles, and occasional musings. No algorithms—just me, writing to you.