A curious journey into flavor, memory, and why our brains keep turning alligator, frog, and turtle dove into poultry.

I still remember my first trip to New Orleans in 2019. I tried a link of alligator sausage and the server assured me, with total confidence, that it “tastes like chicken, just a little fishier.” He wasn’t wrong. I’ve heard the same promise about frog legs, turtle doves, and half a dozen other “exotic” meats. And if you asked me what they tasted like, I’d give the same answer. Somehow, no matter what new animal winds up on the plate, our taste buds reach for the same comparison: chicken. But why?

In the United States, chicken has become the default meat. In 2021, Americans had about 68.1 lbs of chicken available per person, more than beef at 56.2 lbs. (Economic Research Service). Worldwide, poultry is now the most-consumed meat type. By 2019, poultry represented roughly 43 % of global meat consumption — up from about 33 % in 2000. (PMC). Because chicken is so ubiquitous, mild, and affordable, it becomes our flavour anchor, i.e., the baseline we compare everything else to.

But here’s the catch: not everything that “tastes like chicken” actually does. The phrase survives less because of biology and more because of expectation, storytelling, and convenience. When we don’t know how to describe a new meat, we reach for the most familiar reference point we all share. It becomes a linguistic shortcut—sometimes honest, sometimes lazy.

Flavor isn’t just about the animal itself. It depends on fat content, texture, seasoning, and cooking chemistry. A frog leg grilled over open flame might remind you of chicken, but the same frog simmered in garlic butter doesn’t. Alligator tail has a similar muscle structure to poultry, but its mild fishiness only shows up when it’s cooked a certain way.

So the question isn’t really “Why does everything taste like chicken?” but “Why do we insist on saying it does?”

Thus, the chicken-comparison isn’t random. It sits at the intersection of biology, cooking, chemistry, and human psychology.

Many land animals we describe as “chicken-like” share similar muscle proteins, especially myosin and actin, which make up the bulk of lean meat. These proteins don’t carry much flavor on their own, so what we really taste is the way they react when heated. Low-fat, mild-tasting meats (like rabbit, frog, and alligator) brown and firm up in ways that feel familiar on the tongue.

Cooking seals the deal. When meat hits a hot pan or grill, sugars and amino acids create the Maillard reaction—the same browning process that gives roasted chicken skin its flavor. So even if you’re eating something exotic, your brain maps the caramelized, savory notes to the closest reference it already knows.

Psychologically, we’re wired for comparison. If you try a new food and someone asks, “What does it taste like?” you’re not going to describe its molecular structure—you’re going to reach for the nearest flavor metaphor that won’t scare people away. Chicken has become the universal translator of mystery meat. Nothing comes to mind for avocado.

So it’s not that everything tastes like chicken. It’s that chicken is the flavor our brains are trained to return to when things get unfamiliar.

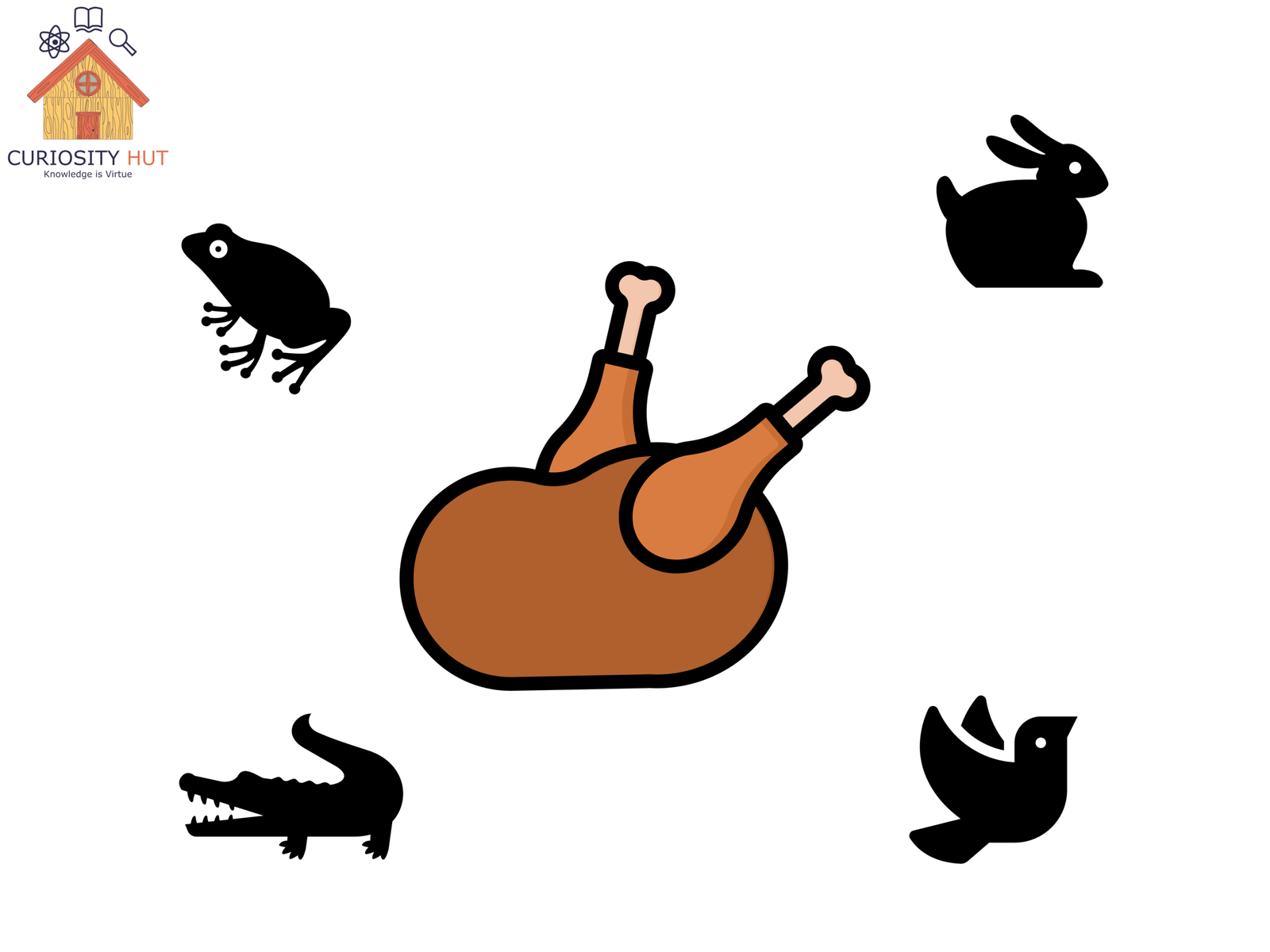

Mini Case Studies – The “Tastes Like Chicken” Hall of Fame

Take a quick tour through some of the usual suspects:

Alligator – Lean, white meat, low in fat, firm texture. When fried or grilled, the surface browns just like chicken breast, which is why most first-timers say, “Yeah, chicken… but with a hint of fish.”

Frog legs – Light, tender, almost no intramuscular fat. The flavor on its own is subtle, so whatever seasoning you add becomes the dominant note. Grilled frog legs taste like grilled chicken. Sautéed frog legs taste like sautéed chicken. It’s culinary camouflage.

Rabbit – Another lean, white meat with mild flavor. The only real difference is in the grain of the muscle—rabbit shreds more like turkey—but when braised or roasted, the savory profile overlaps heavily with chicken.

Iguana, turtle dove, quail – Different animals, same pattern: if the meat is pale, lean, and cooked hot and fast, it will pick up the same browned, savory cues our brains associate with chicken.

Now compare that to foods that never get the chicken comparison: beef, lamb, salmon, duck. They all have distinct fats, strong aromas, and darker muscle fibers that produce richer, sweeter, or gamier flavors. No one bites into a steak and says, “Kind of chicken-y.”

Even insects sneak into the category. When fried, cricket legs and mealworms get crispy and protein-dense, and the browning reaction creates the same roasted flavor families we know from chicken skin. That’s why people often say roasted crickets “taste like chicken mixed with popcorn.”

The rule is simple: when the meat is low-fat, pale, and cooked in a way that browns it, our brain goes straight to the poultry file folder.

Takeaway – The Final Bite

So in the end, everything doesn’t really taste like chicken. We just keep saying it does because it’s the safest flavor we all understand. Chicken became the measuring stick, not the mystery.

The real story isn’t about poultry at all—it’s about how we use familiar tastes to navigate unfamiliar worlds. And as we move toward lab-grown meats and synthetic flavors, maybe one day the default won’t be chicken at all. In a world where even our food is engineered, perhaps we’ll be saying, in true Orwellian—or Huxleyan—fashion: “It tastes like what we’ve always been told to taste.”